The big idea: a tip jar for scenic neighborhoods

A big idea to compensate residents of tourist towns for the externalities that tourists bring.

Some towns are so beautiful that they inevitably become tourist attractions.

Places like Venice, Santa Barbara, Barcelona, and Monterey all have scenic neighborhoods filled with residents who enjoy the picture-perfect environment. It seems idyllic, until you realize that the price of paradise is a never-ending stream of tourists.

The residents of these towns seem to hate their tourists with a passion. Tourists are blamed for everything from rising rents to expensive restaurants, but most importantly: they are considered annoying to have around.

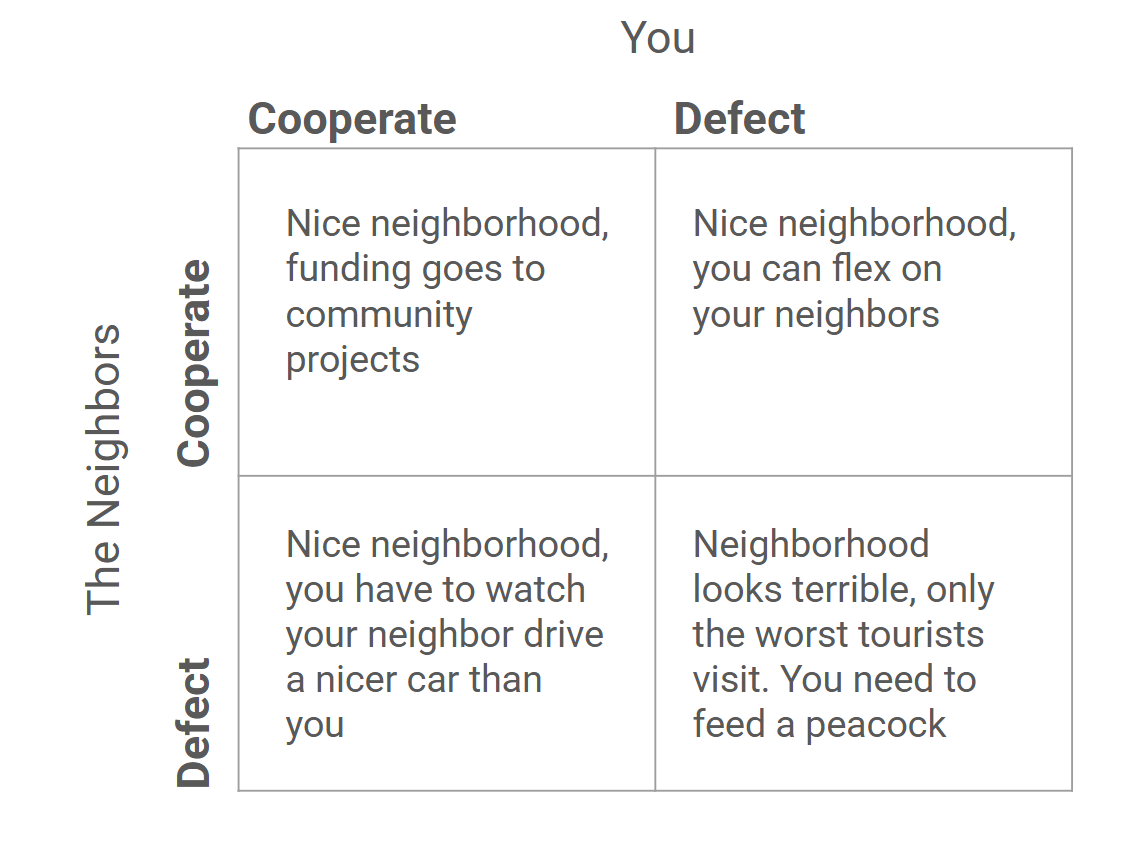

Ironically, the very things that make these cities nice to live in attract the tourists that ruin them. Those picturesque neighborhoods are, in practice, a public good provided for free by the people living there.

The better they keep up the charm, the more annoying tourists they need to deal with. Any benefit is captured by local businesses, cold comfort for a retiree. For a tourist hater, the rational response is actually disinvestment: why beautify your house when it means you need to keep your curtains closed to hide from nosey tourists?

This seems like a problem. One idea to fix it: ask visitors to tip the residents for maintaining the charm they came to see.

Tourism can sometimes feel like an extractive industry

Tourism has surprising similarities to extractive industries like oil or timber. Locals live near a resource that’s primarily consumed by outsiders. Infrastructure is built to support the industry over residents. There are externalities to quality of life nearby, as the natural beauty of the place is disrupted.

Sure, a remote oil well (usually) is less disruptive than a million tourists in your home town. But while you’re not clear cutting the forests, the selfie line by the trees still has a cost. Paradoxically, as local economies become reliant on tourist dollars, you tend to see greater pressure for tourist-hostile actions like an Airbnb ban or aggressive protests.

Reasonable people can argue whether tourism is a net benefit. It clearly has economic value — Venetians might hate tourists, but that doesn’t change that tourism is 85% of their economy. Still, there clearly is some level where over-tourism begins, other local industries are replaced, and the quality of life deteriorates from overuse. Charming cities like Venice and Bruges have started taxing visitors directly to control millions of visitors eroding quality of life.

Externalities abound as tourism explodes. It only seems fair for tourists to compensate residents, but maybe we can be more creative than a €4 tourism tax.

The neighborhood tip jar as voluntary compensation

Unlike a traditional pay for service model, which charges for entry, the neighborhood tip jar uses social pressure to get drivers and pedestrians to pay up. As tourists turn onto the street, a sign with a QR code politely asks for a donation to maintain the quality of the road.

The QR code lets visitors Venmo or Cashapp an account run by the neighborhood association, which manages the collected money. Operating like an HOA, the neighborhood association elects a board that decides how money is distributed.

Neighborhoods could opt to distribute the money as cash to residents, but some might reinvest the money into the neighborhood. Think public amenities like swimming pools and playgrounds, flower beds for everyone to enjoy, or pristinely maintained sidewalks. The braver ones might use the money for new infrastructure to separate tourists from their homes, financing backyard porches that hide them from the annoying “Historic Downtown” walking tours.

This could legitimately raise real money. A study in Sweden found that mountain bikers gave an average of ~$10 based on a signpost asking for a donation. 71% of visitors to a cathedral in England donated, with an average donation between £1-£2. A marine park in Portugal was able to raise around $0.40 per visitor for charity just by throwing up a poster.

There’s a multitude of behavioral economics research for neighborhoods to leverage in driving donations. Museums have mastered a range of techniques that anchor guests on higher donations (think “suggested donation: $4” or “it costs us $3 per guest to maintain the museum”). Reciprocity is a powerful force — if you tell someone you’re giving them something, they feel a need to give back.

It seems reasonable that framing a visit to a picturesque neighborhood as consuming a good that residents provided could work. Some of these neighborhoods get several million visitors a year; if donations looked like the Portuguese marine park, top neighborhoods could pull in over $400,000 per year.

With a financial incentive to bring in guests, some neighborhoods may opt to maximize tourism. Streets that aren’t widely known might add themselves to Google Maps and start pitching themselves to Lonely Planet for the “cute neighborhoods to check out in Charlotte” list. Entrepreneurial neighborhood associations could start plastering those obnoxious “rate us on TripAdvisor” signs at the street exit.

Over time, residents might even start investing in new tourist attractions. Green St might become the new home of the world’s biggest pair of glasses, or a bootleg botanical garden facing the street. Beautification projects start competing as neighborhoods collectively invest in whole reams of tourist infrastructure.

But the new pressure on the town — additional demand for hotels, restaurants, road usage, and more — feels like a big risk. Not every resident is going to be on board with bigger and better; hatred of tourists seems destined to reemerge, even if they’re paying up.

Maybe it won’t have the chance to get to that point. There’s going to be competition for these tourism tips: if one house is the main attraction, why would they share with anyone else?

The enclosure of the neighborhood commons

Once there’s real money on the table, the logic of neighborhood cooperation starts to fall apart.

Imagine Maple Street has their tip jar, money is coming in, and the association has funded a garden project. Ellen at 442 Maple is an aspiring gardener, and did a particularly tasteful job with the tulips. She gets tagged on Instagram, takes off on Google maps, and suddenly visitors are coming to Maple Street just to see the locally-famous 442 Maple Gardens.

At this point, Ellen might reasonably go to the neighborhood association and demand a bigger cut — after all, the donors are coming to see her garden. The neighbors — who want to be compensated for the additional foot traffic — refuse. Negotiations break down. The next day, 442 has their own QR code up.

This is a disaster for the Maple St Association, who see their donations rapidly cannibalized by the savvy business sense of Ellen at 442. She starts pulling in real money, driving fancier cars around and getting new furniture delivered. Greg across the street at 445, sees this and thinks: “why can’t I do that?”

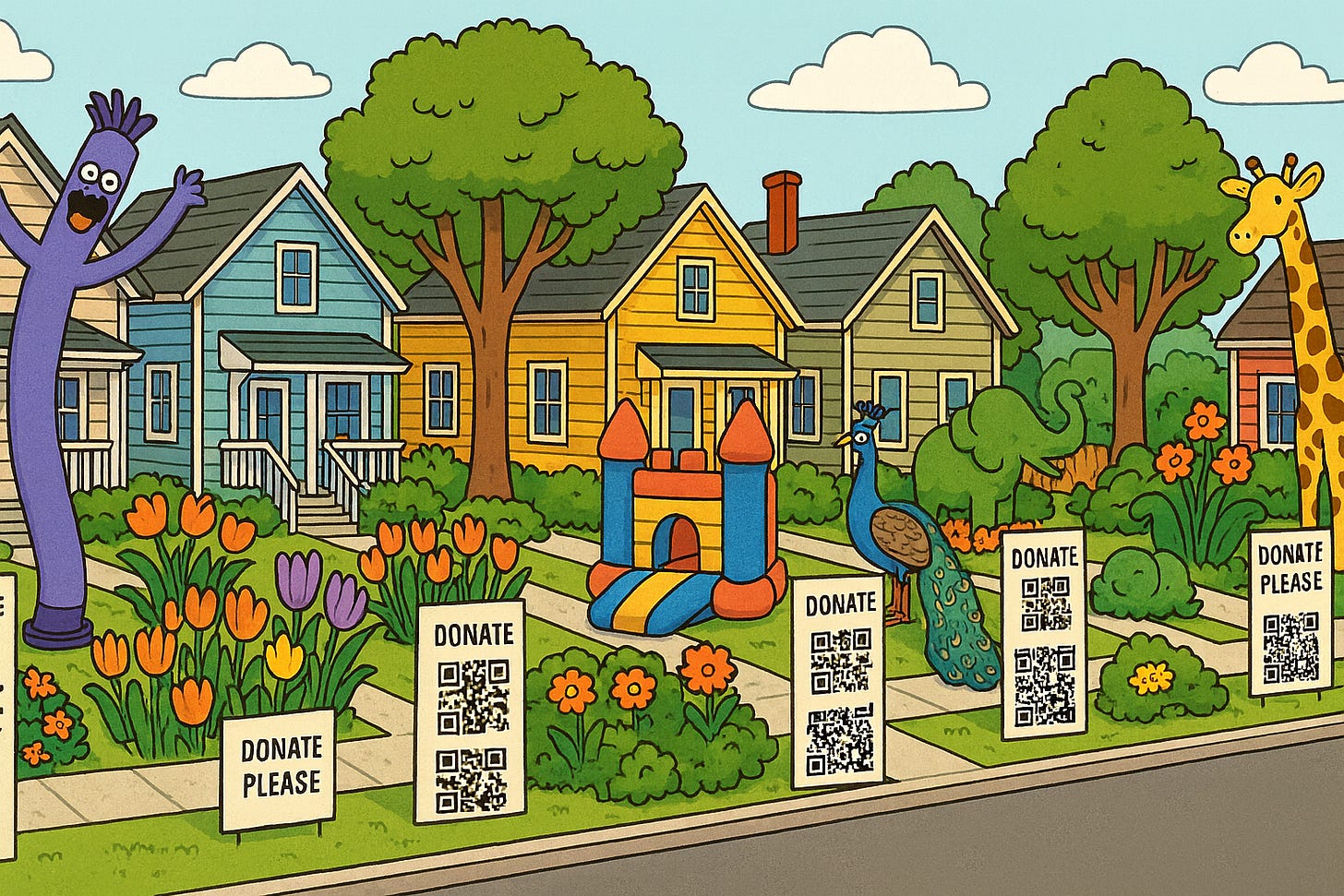

The next day, 445 has a peacock. After a week, 452 sets up a bouncy castle. 417 starts offering driveway goat yoga. The race is on.

The HOA tries to sue, but the offending houses have enough tip money that legal battles drag out for years. And with each defection, someone else thinks: why not me? Soon enough, Maple Street is a collection of houses with no clear cohesive theme. Tourists start to think of it as kitschy, stop donating, and the neighborhood is left looking sorta like this.

Maple street has reverted to its Nash equilibrium. Before the tip system is proven, the benefit of defecting is basically $0. You’re just putting an ugly sign in your front yard next to the tulips you’re presumably excited about.

But if Maple Street starts bringing in real money, the temptation to privatize becomes real. Any one individual with a good attraction can defect, and cooperation breaks down. The commons collapse into chaos.

The only stable equilibrium might be a QR code on every mailbox and dozens of competing walking tours. Or more likely, a strict HOA that stops the sign from going up in the first place.

Official idea rating

2/5. Don’t expect to get your neighbors on board, but if you have a really great garden slap on a QR code and see what happens. It might work out for you.

Modern tourism is a tough balance. Charming places are shared, commodified, overextracted, and become shells of themselves. But at the same time, the economic benefits become the lifeblood of the town — impossible to remove without killing the economy for those not lucky enough to retire there.

Cities are already exploring new ways to control tourism and properly internalize the externalities they cause. The bottoms up solution today seems to mostly be getting in on the gold rush or trying to shut it down. Maybe a combination of QR codes and social pressure is the technological solution we’ve been waiting for.

Isn’t this what sales and hotel taxes are for?

Overtourism is an externality at the municipal level. Taxation prices that in.

Turning some of the revenue into a rebate for taxpayers completes the incentive loop.

The owner of the homes and the neighborhood did not create the touristic value. They mostly inherited it. They bought into it when they purchased their home. This is a classic example of pulling up the ladder. They bought because of how charming it was and are then annoyed because visitors who pay state and local taxes also want to experience that neighborhood. This is more like the people who buy near an airport and then want the airport closed because of the noise. If you don’t want the tourists, don’t buy in a touristic area. I estimate 98% of homes are in neighborhoods that never have tourists. Those who complain are trying to drive up the value of their homes after purchase by getting the great neighborhood AND no tourists. No.