The big idea: Make everything harder to use

Taking the time to do something is a signal that you value it. What should we do when AI automates that away?

For decades, restaurant reservations were done over the phone. Having occasionally done this, it was sort of a crappy experience — you had to go back and forth on times with the other person, trying to be heard over the background noise. If it turned out that nothing worked, you needed to find another restaurant to call.

A lot of this pain was removed with the introduction of OpenTable and Resy. Suddenly, you could see every open spot and make adjustments on the fly. If your first choice of restaurant is full, the platform suggests another one. There’s no need to talk to anybody on the phone, opening up restaurant reservations to a new class of socially anxious people that had presumably been eating at home.

But this improved experience came at a cost. The number of no-shows at restaurants have skyrocketed; according to OpenTable 28% of Americans said they no-showed at least once in the last year. This isn’t just careless people: restaurant reservations are valuable, and scalpers have begun hoarding the most in demand tables for resale. In response, restaurants have begun to implement deposits and cancellation fees.

Why did this happen? Technology removed the friction that separated the signal from the noise. Friction isn’t just an annoyance: as the reservation process simplified, the cost of a reservation you’re not sure you’ll use falls. Eventually, making a reservation goes from a signal of high intent to eat there to a medium intent to eat there — and the whole system breaks down.

The same thing is happening everywhere. Concert tickets are picked up en masse by scalpers, causing platforms to add superfan waitlists. Rental car dealers add stricter cancellation policies. Tinder punishes you if you swipe right too often.

AI is accelerating this process by reducing friction across every platform with a digital access point. And that’s making the issues of a frictionless world worse.

A theory of friction

Obviously to some extent, friction is bad – removing it increases access to customers and cuts the cost of doing things, making people richer and generating economic growth. But it’s not a free lunch because of the law of conservation of friction: friction is never fully removed, just reallocated.

Take job applications as an example:

A party removes friction: LinkedIn introduced Easy Apply, making it much simpler to apply for a new job. This removed friction, bringing in marginal applicants.

Removing friction increases use: Many more people applied to Easy Apply jobs, even those they might not be particularly excited about.

Lack of friction introduces new costs: With more applicants for each job, it becomes harder to be seen. Candidates get frustrated as recruiters struggle to manage hundreds of resumes.

Abuse vectors enter: New AI apps emerge to mass-apply for jobs automatically, expanding the deluge of applicants for every job.

Behavior changes: Those that don’t adopt the mass application start to lose out to those who do, causing them to either adopt new tools or apply to even more jobs.

New bottleneck emerges: The number of applicants drives recruiters to use AI screening tools, rely on referrals, or extend the hiring process to interview an endless supply of miserable candidates.

Maybe for the first time, we’re starting to confront a downside of too much access and ease of use. This is a pretty radical departure — the purpose of innovation for almost all of human history has been to make things easier!

What if there was a simple way to add some friction back across all kinds of digital services? Imagine a Universal Friction Interface (UFI): a plugin that lets platforms seamlessly make themselves slightly harder to use.

Ways to create intentional friction

A UFI would simplify the process of adding friction back into digital life. When submitting anything — an application, a purchase, a reservation, or a swipe — the UFI dynamically adds in a barrier to completion. In the same way Stripe lets anybody set up payment infrastructure, UFI lets anybody set up friction infrastructure.

To help companies find the right solution, a set of small annoyance functions (SAFs) need to be developed. What might these look like?

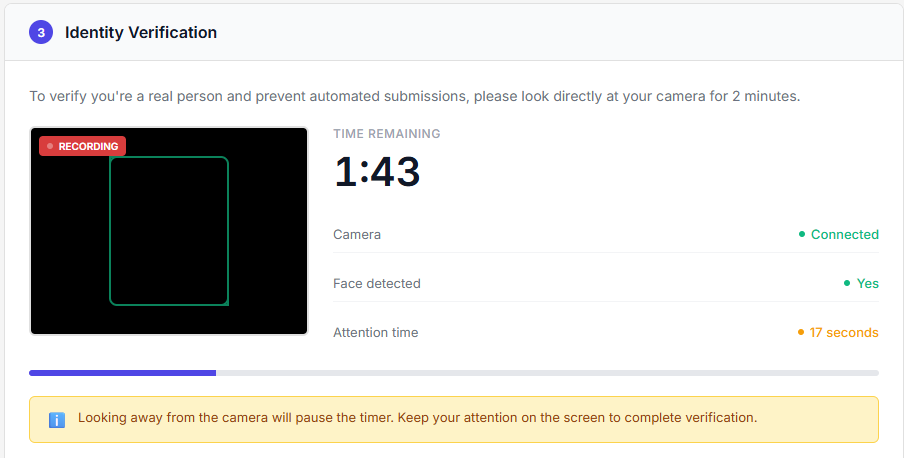

Attention meters

Before the submit button can be used, the user turns on their webcam. The applicant is required to stare into the camera for an adjustable period of time — say, 2 minutes. Eye tracking software will pause the timer if the person looks away.

On its own, 2 minutes is not particularly long to wait to do something you’re really interested in, but it’s just annoying enough to stop you if you’re meh on it. By requiring a human time investment, the attention meter short circuits AI-driven automation.

This is ideal for any high-intent use-cases: job applications, house tour requests, or even sending an email to in-demand recipients. As a bonus, this gets UFI into the digital detox market.

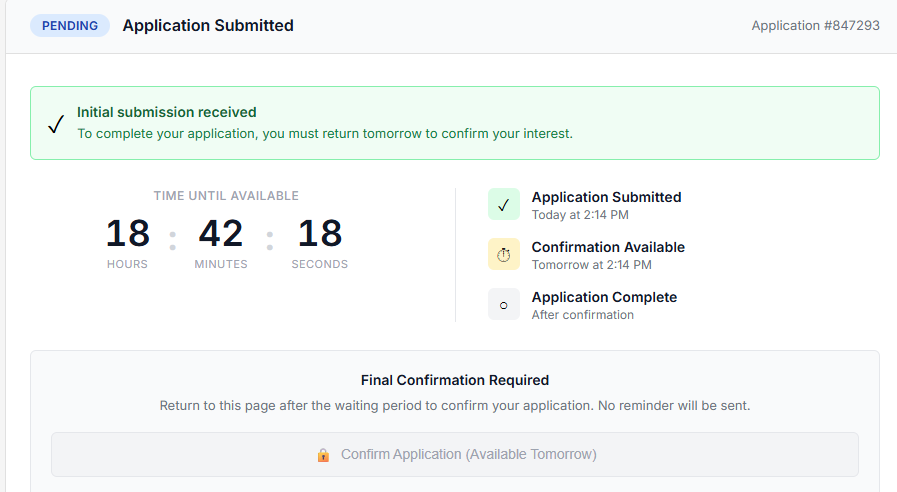

A cooling off period

After submission, applications enter a 24-hour hold. No reminders are sent. Users must return the next day and resubmit, proving they care enough to follow through.

This might be suited for things that suffer from impulse actions. Think items with high return rates, exclusive membership groups, or in-demand jobs. A cooling off period can filter out those that would have backed out anyway.

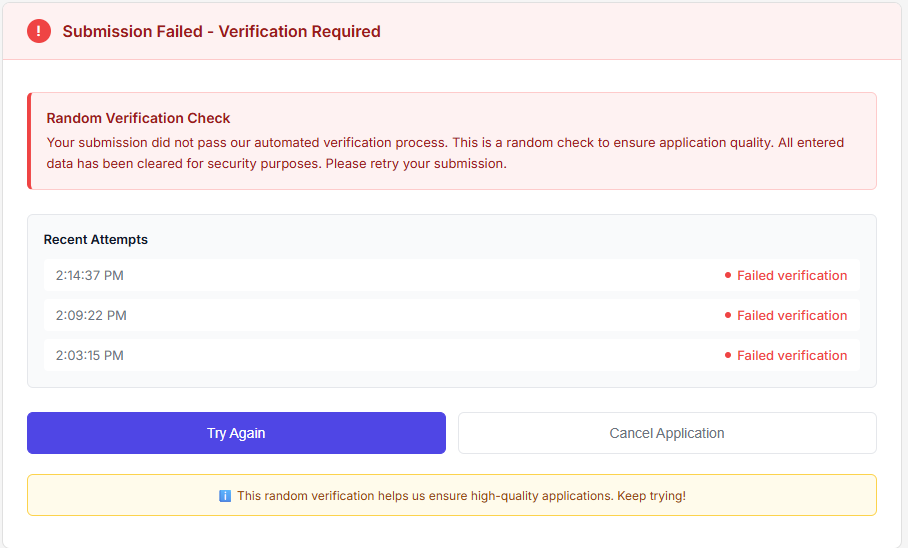

Probabilistic Resets

After finishing some process — a checkout flow, an application, etc. — users need to hit submit. A dynamically adjusted percentage of attempts automatically fail. Unlucky users are logged out of their account and all of the information they’ve entered is reset.

This is a pretty annoying experience, but is theoretically fair: everybody has an equal chance of having their process reset. To avoid bad luck driving some users insane, there could be an increasing success rate after N attempts.

Why would we do this? There’s some optimal mix of high and low intent people; by making it random, you can control the rough ratio of users that fall into each category. The sunk cost fallacy will hit high intent users, keeping them retrying until they go through.

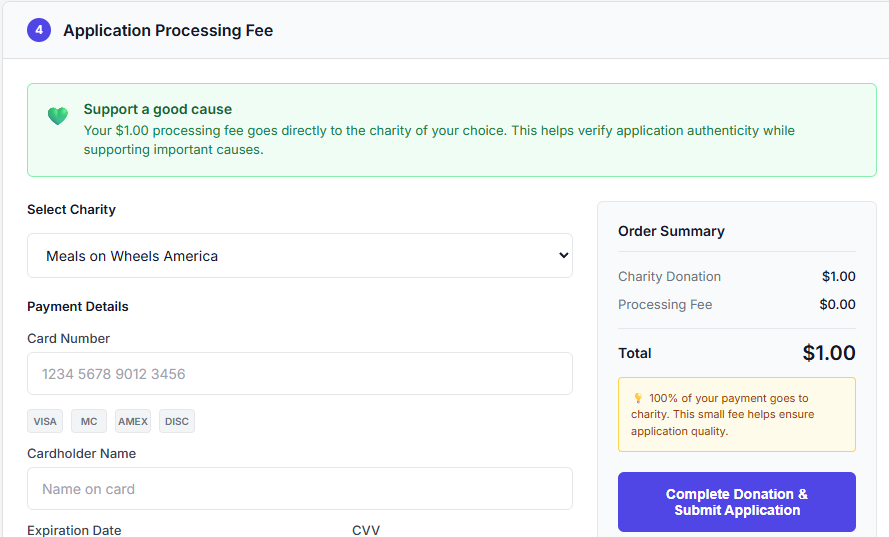

Just charge them $1

We’ve covered this elsewhere, but monetary impacts don’t just have to be draconian charges for no-shows. A small upfront fee — even if paid to a third party like a charity — can bring more friction than the sum of its parts. In addition to being a little bit of money, the pain of adding a credit card is enough to scare off low-intent users.

You could even skip charging the $1, and just add the pain of entering credit card details. This isn’t a new idea; some free online games charge a nominal amount to deter cheaters, since you eventually run out of unique credit cards to use.

Physical mail confirmation

Print out a QR code and mail it into a service. Dealing with printing and mailing something physical shows the type of conviction that makes you pretty confident someone will show up to their restaurant reservation.

Now, I can acknowledge that users will hate any of these options — you’re explicitly making the product more annoying to use! But this might be a case where revealed preferences outweigh the initial reaction. It’ll be annoying, but the services that adopt intentional friction are going to have some advantages over the ones that are plagued with scalpers or rely on charging outrageous fees.

Is there a real business here?

Possibly! Average restaurant no-show rates are 15%-20%, but let’s be generous and use Resy’s reported no-show rate of 3.5%. Applied to Opentable’s 1.8b diners per year, that implies 63 million people don’t show up for a reservation every year.

Opentable charges $1 per seated diner; if friction can reduce that by 50%, that’s $32M in revenue created. Apply that to every dating app, job application, and reservation system in the world and there starts to be a meaningful amount of value created. It may not be enough to be the next Stripe in size, but it’s probably enough to build a sustainable business.

Sure, some of this could be done in-house by existing product teams. But I don’t think it’s going to be particularly popular to have a team work on making products harder to use; the internal politics of companies might serve to stop them from creating a dedicated friction team. Nobody creates their own CAPTCHA system; it’s not that crazy to outsource bits of a submission process.

Beyond the effort, specializing in friction has other advantages. It’s hard to imagine that making products harder to use wouldn’t prompt lawsuits in the US and regulation from the EU. Being the only company that makes things hard to use compliantly is a pretty fair moat.

The impact of adding friction

Getting UFI adoption would be a slow process. Most companies have an issue with not enough interaction, not too much.

The first stages would be for markets with high demand and low supply. That could be job applications for entry level roles, in-demand concert tickets, or hotel reservations on big event weekends.

If adding friction is successful, it might have an unexpected effect. With more friction, high intent users will get first dibs at the services that adopt it, which are likely to also be the most in-demand. With high intent users moving to a limited set of items, the remaining pool of people will be lower-intent on average.

That means the no-showers, cancellers, and mass sign-uppers will concentrate on the laggards at adopting friction. With more and more issues, mid-market businesses might begin to add friction to better filter.

Eventually, social norms could begin to shift; reservations without friction will look suspicious: “why don’t they value a reservation enough to make me stare at the screen for 30 seconds? The food is probably bad there!”

Of course, all of the same trends that have erased friction up to this point will work against attempts to reinstate it. Tools will emerge to work around the new, artificially frictitious regime, requiring ever increasing complexity to maintain the effect. Stubborn people might begin to adopt eye spoofing software or pay somebody to stare at the webcam on their behalf from a foreign country. Although the effort to set this up is, in some ways, a friction in itself.

This back and forth between added friction and its workarounds is likely to continue indefinitely, but it’s a fight worth having. If we can’t nail it digitally, the future might be a bit more physical — mailed in job applications, oral exams, and in-person merch drops.

Official idea rating

4.5/5. The mass removal of friction that AI drives is going to bring a counterreaction, and someone will need to develop methods to bring signal back in a world where more and more of what you see is AI-driven noise.

Without intervention, pay-for-play and tight networks of people seem likely to become the de facto filter, perpetuating existing networks and status as a method to pare down neverending information. Or it could go the other way, with AI regulating endless slop in a black box that individuals can’t understand.

Against these alternatives, adding in artificial difficulty might be the least-bad option. It just remains to be seen whether someone can build a company on friction, hostile UX becomes a new PM specialty, or we all just pay more fees.

The best thing about this idea is how much I hated it.

Like, at least it's proposing something with an actual impact, because why else would I (or anyone) care about it?

That said, I think everything besides "money" is probably a non starter. I can already spoof an AI video to stare at a camera's input feed for me (and would definitely do that, and would happily spin up a service for normies to do it at 50 cents a pop or whatever).

Cooloffs and probabilistic resets only whack humans, any AI or program filling in and spamming stuff is completely undeterred.

Mailing stuff in and money are probably pretty solid. No spammer at scale can afford to spend $1 per throw on whatever bullshit they're doing, and physical mail should work as long as the thing isn't high value enough to merit services or faking (for instance, there are almost certainly services where you can send them a digital picture of the thing and they'll print and mail it for you, any Staples / Fedex / whoever does this already).

As you point out, the overall idea of friction as a service is mostly about separating people who actually care from tire-kickers, and money or deposits probably does that fine already, and it might be tough to expand to the more digital use cases (or the digital "attention" currency, god help us, how would this not be immediately exploited at scale? Like people don't waste enough of their lives staring at the blinky box already? I probably just don't understand what's being proposed there).

I think the lack of friction is a big reason why social media has such a low signal-to-noise ratio now. Since people can get paid for content now it has added even more incentive to use exploits when vying for attention. I think that Substack has tried to steer clear of this dynamic by making email subscriptions the main channel of interaction, but there is a feed and it seems like more of the casual people I know on Substack default to this mode of operation. My hope is that every platform doesn't have to resort to algorithmic recommendation and feed-style presentation to achieve scale and a sustainable business. It does seem like this is the default end state, though.