A marketplace for trading chores

We live in a trillion-dollar autarky where everyone is sort of bad at their job. What if people were willing to trade?

I absolutely hate organizing my closet. It’s everything I don’t like in a chore — hard to begin, difficult to stop once you start, and easy to put off to another day.

What’s annoying is that I’m sure somebody near me would love to organize my closet! Marie Kondo built an empire with people who find joy in organizing things. I know they exist!

Sure, I could hire someone. But non-specialized tasks can be hard to justify paying for. It’s easy to pay someone to do your taxes when TurboTax can’t handle it; it feels a bit indulgent to pay someone to sort your recycling. And that’s assuming you can afford it.

That’s not to say that all chores are bad. Personally, I don’t mind meal prepping. Why can’t I make an extra large batch of chili and sell it to my neighbor for some vacuuming?

My pitch: Chorely, a marketplace to trade the chores you like for the ones you don’t.

Chores aren’t like other markets

Chores are an almost unique type of labor. Inside every home is an autarky where the inhabitants do a bit of everything. At best, they split it with their partner or roommates.

No other part of the economy really works this way. A lawyer wouldn’t spend two hours cleaning their office: they’d hire a custodian. But somehow, when it’s in the home they’ll pull out the mop without thinking twice.

On average, Americans spend 208 hours per year on household work; with ~350 million Americans, that’s 72 billion hours per year. Assuming $15 per hour, there’s over a trillion dollars per year operating in pure autarky — a bit more than the GDP of Poland. We’ve created a top 20 global economy where everyone is kind of bad at their job.

There are obvious benefits to bringing trade to this market. I’d be happy to swap doing laundry for somebody else deep cleaning my pans. But these types of trades almost never happen today.

Liberalizing chore marketplaces

The basics of Chorely are pretty simple: allow bartering in the chore economy. The app lets you find nearby people who want to trade chores, negotiate trades, agree on a time, and confirm completion. Afterwards you rate and review the quality of the job they did.

It’s a simple idea that hides a lot of economic complexity. Bartering requires a coincidence of wants; not only do you have to want the chore I’m offering, I have to want the one you’re offering. One solution to this is to allow for multi-person trades —I do everybody’s meal prep in exchange for person A doing all of our organizing and person B doing all of our cleaning.

But as this scales to more and more people, the organizational costs increase exponentially. I don’t really want 25 different people coming to my home, each doing a specific chore. Also, it’s not like all chores are equal; how do you account for a unit of deep-cleaning the shower being 1.3x the value of cleaning the coffee machine?

You might be asking: “why wouldn’t we just do this all with cash? Wouldn’t that simplify everything?” Well, at that point you’re basically recruiting people to be Taskrabbits. With cash, market prices begin to converge on the market prices for home services — unaffordable for many of the people who would be interested.

Even if it were affordable, cultural norms shape who is willing to supply chore labor. Lots of people who might be willing to organize a desk to avoid cleaning a litter box wouldn’t do the same for $8. Call it snobbiness, but selling unskilled labor is something that lots of white collar workers just won’t do. Their labor exists in terms of exchange: they work a job, get some money, and use that money buy services from other people.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Uber unlocked driving to a group of people that would have never driven a taxi. Airbnb unlocked hosting to a group of people who would have never worked in a hotel. Maybe direct exchange will give people the social permission structure to do some chores for their neighbor. Bring on the spirit of 2012 and change society through an app.

Still, it might be a bit easier if we didn’t have to do everything through bartering. Like the evolution of barter to currency, we need a unit of exchange. Let’s call it the ChorePoint.

A currency for chores

Say that you’re trading with someone named Greg, who is offering plant watering for dishwashing. You want to have someone water your plants, but it’s just not a fair trade — plant watering isn’t that big of a deal to you. You could come up with some complex trading algorithm like 3 dishwashings for 8 plant waterings, but the coordination and negotiating costs skyrocket. Instead, you might agree to trade a dishwashing for a plant watering + 50 chorepoints.

Suddenly, a whole new universe of trades are possible. Not every chore has to be directly traded; you can dishwash for Greg and trade it for vacuuming from Sally. It also means that chores can be traded over time — you can exchange snow shoveling in the winter for lawn mowing in the summer.

To get these trades rolling, we need to solve the cold-start problem. When the platform launches, nobody has any ChorePoints to spend. So how do you seed a brand new currency?

A traditional platform might start by giving users some free points, but this creates the risk of inflation and bad behavior. Other platforms have to constantly fight users creating phony accounts to use signup bonuses and never come back. Or Chorely could sell ChorePoints for cash, but that’s just Taskrabbit with more steps.

Maybe the answer is to keep following the traditional economics 101 historiography: after bartering and currency comes debt.

Fractional reserve banking for chores

At the creation of your Chorely profile, all users start at 0 ChorePoints. But that doesn’t mean that there’s no way to use ChorePoints — every user has the ability to go 500 points into debt. The catch: debt levels are publicly visible as part of your profile for each chore trade you do.

With this decentralized fractional reserve system, each individual user can do the equivalent of creating 500 points out of air. It’s not a free lunch: users in heavy debt can face social signaling of being a high risk trading partner, with consequences like lower search rankings for ChorePoint-negative offerings.

Over time, this actually becomes a natural risk assessment. It seems reasonable that you’d want to trade with the same people consistently after you’ve built trust. Someone in significant chore debt becomes a major credit risk for a long-term partnership.

Managing a healthy economy means encouraging sufficient trading of goods and services. For the chore economy, Chorely needs to act like a central bank. By changing reserve requirements (e.g. allowable debt), the company can indirectly influence price levels. If there are insufficient trades, it might make sense to allow more debt to drive a little inflation and get people trading again.

These prices are going to be set by the market, but this is a movement from autarky to trade. What can traditional economics teach us about this change?

An economic model of chore allocation

Trading chores isn’t so different from countries gaining advantages from trade.

Classic Ricardian comparative advantage is a simple model that says that countries should specialize in goods where they have the lowest opportunity cost (e.g. the value of what they could have produced instead). This is true even if a single country is better at producing any given good, because your total productive capacity receives gains from specialization.

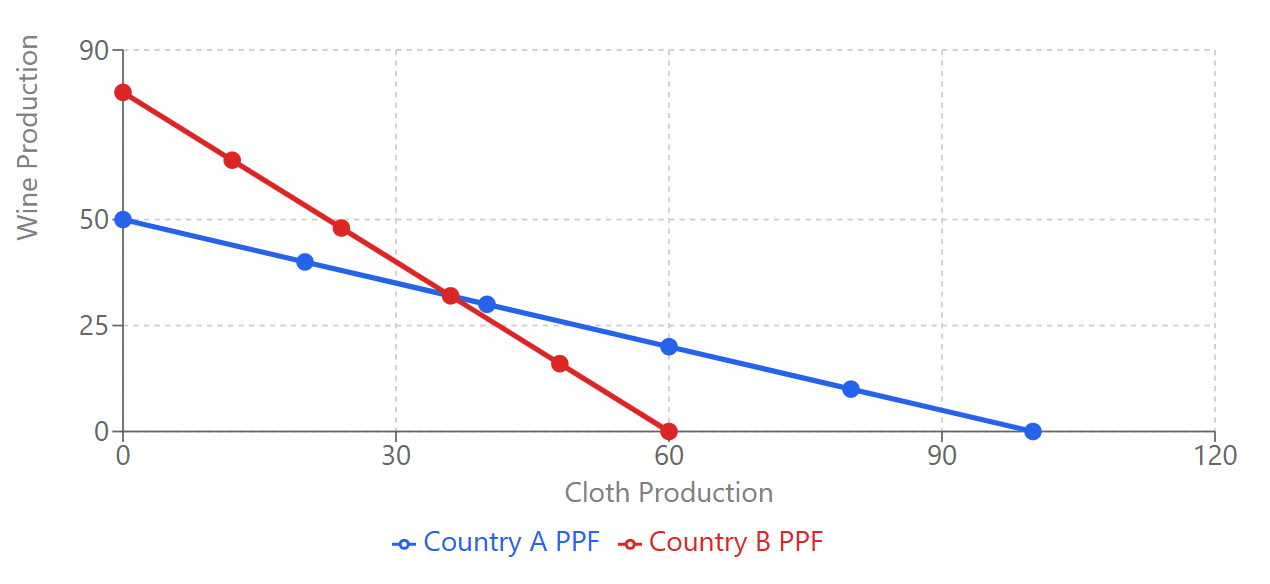

If you remember econ 101, it sort of looks like this1:

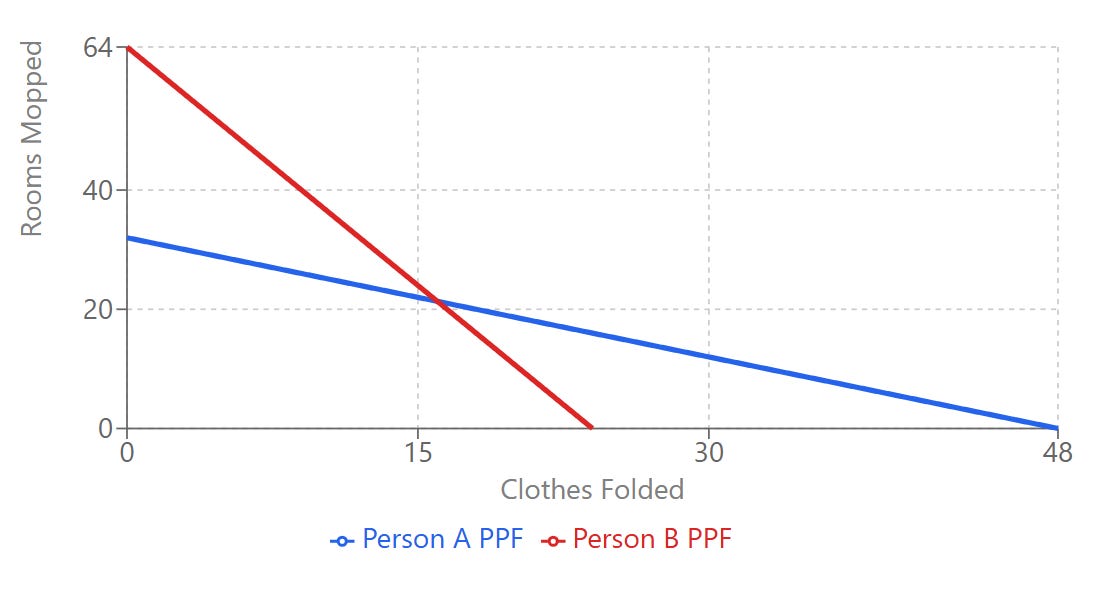

Chores sort of work on the same principle…but also not really? If you applied Ricardian comparative advantage to chores, you would primarily be focused on your relative output in terms of speed. If I can do two loads of laundry in the time it takes to organize the closet, then organizing the closet is worth 2 loads of laundry.

But what if you hate doing laundry with a passion? Trades aren’t just a matter of productivity; we need to account for relative distaste using the burgeoning field of NDIan comparative tolerance.

Unlike traditional Ricardian economics, NDIan comparative tolerance doesn’t just care about efficiency. On top of the time something takes, a pain coefficient is multiplied to account for how much you think a chore sucks. If mopping is twice as miserable as laundry but takes half as long, you'd be indifferent on which one to do.

\(Time_{Chore} * Pain_{Chore} = Adjusted \:Chore \:Value\)

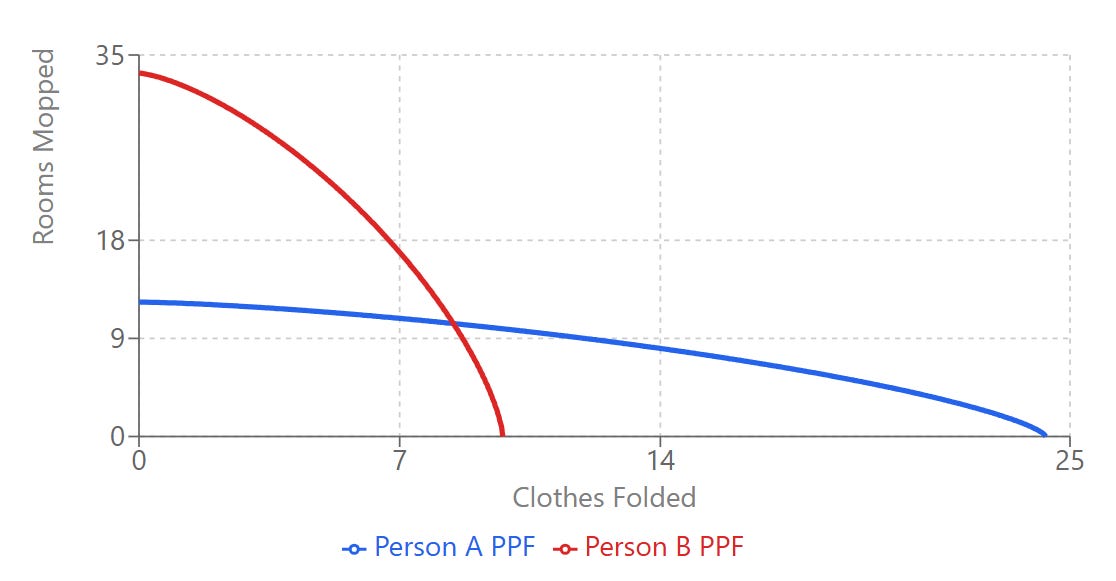

We also need to account for burnout; you could be fine doing dishes for 30 minutes, but after the 4th hour you might be dying to do anything else. Let’s call this burnout coefficient β, an escalating misery that comes from more time on the same chore.

So while previously a tradeoff of mopping and folding clothes might look like this:

Under our burnout system, it looks more like this:

This economic model tells us a few things about chores:

Time isn’t the only factor; at some point, you’ll do the thing you hate for 10 minutes over the thing you like for 3 hours.

The optimal tradeoff for most people isn’t pure specialization; you might only trade at the margins to avoid the most painful chores to you

Any burnout dramatically reduces the total amount of chores you can do. You might trade away your most hated chore, but that doesn’t mean you want to do dishes 500 times in a row to avoid something you just sorta-dislike

While these all get aggregated out over time on the app, these are a lot of new considerations for people doing the Chorely system. Our product manager will need to incorporate a lot of behavioral psychology in their product design.

And I guess there are a few practicalities

When I pitched this to my wife, her first reaction was “why would you let a stranger into your house?” She argued — and I guess she’s right — that it’s different letting in a professional cleaner than some stranger down the street who offered to take out your trash.

She has me there, but it really highlights how weird the current system is. We’ll let a Taskrabbit in without thinking twice for $25/hour, but trading dish duty with your neighbor crosses a line. Money launders trust, but direct reciprocity feels unsafe. Even weirder, this actually scales — the more you pay, the more you trust your counterparty to be honest.

Of course, there does need to be some margin for safety. Platforms like Airbnb and Uber spend immense amounts of money on insuring the risk that comes with bringing millions of strangers together. This is worth it because each individual supplier will do many trades.

For Chorely, it’s not so clear who would pay for liability insurance, and who is responsible for vetting the people in their home. Even worse, you might be bringing in a dozen people to cover the full gamut of chores; the transaction and operational costs are brutal.

One idea is to solve this trust problem and monetization in one go — what if Chorely became a financial institution?

Chorely Pro is the option for real chore-heads trying to outsource the chores they hate the most. Pro users — for a low monthly fee — get access to a preferred liability insurance rate, sold and provided by Chorely’s insurance arm. As an insurance company with a chore marketplace attached to it, Chorely can make money through the float on the presumably immense amount of cash that will come as Chorely takes off.

Beyond insurance, there’s clear opportunities to do other upsells. If the boiler needs to be adjusted over and over, that’s a hot (and valuable) lead for a PE-owned home services business. If the bathroom needs weekly cleanings, serve ads for gut health providers. Chores are some of the greatest insights into the state of a home. Someone is going to be willing to pay for it.

Official idea rating

3/5. I want to love it, it’s clearly a broken market where there are benefits from trade. But I think the organizational and practical challenges are a little too high for it to survive in this iteration. People just really don’t want a stranger in their home, even if you tell them it’s irrational.

Still, I think there is something about the idea of service-for-service as a way to launder work that people otherwise wouldn’t do. Lots of people who wouldn’t sell their time to do cleaning would be happy to make the trade with a spouse. How many other trillion dollar markets are locked behind social expectation on who you can trade with?

Short of getting more people married based on their relative NDIan chore preference, the amount of wasted value will only increase. That said, social expectations evolve. Maybe one day, trading chores will feel as normal as calling a rideshare.

In this model, each country can produce a tradeoff of wine and cloth along the line. But country A is relatively more productive at making cloth (roughly 0.5 units of wine for each unit of cloth) while country B is better at wine (roughly 1.33 units of wine for every unit of cloth). They can both make everything themselves, but if they specialize — A does only cloth and B does only wine — and then trade, country A gets an extra 5 units of wine and country B gets an extra 7 units of wine

Solving Baumol's cost disease by psychologically separating the labor from the labor market, kinda makes sense! I think part of the problem here is many people never even bother to check how much it would cost to hire out some of these services. When I moved out of my last apartment we hired a cleaner to do a big deep clean (on the theory we'd be more motivated to find a cheap cleaner than our landlord spending OPM), and it came out to $100/ a head. Not saying that's someone I'd hire every week, but once a quarter? Definitely. I'd just never considered it because having a cleaner feels extravagant.

I have a friend who worked in BigLaw in NYC, and he said on his first day they sat all the new associates down and said something to the effect of "starting today you will hire a house cleaner, you will send your laundry to the fluff and fold, you will order your groceries on instacart. It's going to feel wrong but trust you me you won't last ten minutes trying to do this job and keep up with household chores." Maybe more workplaces should have some version of "the talk" for all of their new employees who have moved from "person living on ramen and debt" to "burgeoning yuppy" in the space of, like, two weeks.

Isn’t this basically Fiverr?

Also, this tangentially reminds me of how my mom ran our sibling disputes like a courtroom. We’d do opening statements, call witnesses (our friends), cross examination, present evidence (broken toys, whatever), and then closing statements and a ruling.

It wasn’t perfectly fair but it did help us feel like there was an actual process.