A priority pass for bathrooms

Is there a better way to operate semi-public bathrooms?

The dirtiest grey market in the world is semi-public bathrooms — places like hotels, restaurants, and Starbucks. These bathrooms exist in a state of semi-formal usage, between a public restroom and customers only.

It’s an awkward and unjust equilibrium. Because the etiquette isn’t clear, it’s a tax on courtesy. The socially awkward pay $5 for a coffee they didn’t want, while the shameless just walk in and ask for the code.

The current alternative, public bathrooms, can be pretty gross. Worse, they’re rare and unreliable, often closing at weird hours. New York City is trying to fix this, passing a bill to build roughly 1,000 public bathrooms over 10 years. It’s a good cause, but at a current cost of a million dollars each I’m skeptical they’ll all get built.

What if there was a third way? Could we simplify the social etiquette while providing exclusive access to the world’s finest toilets? Introducing: BathPass, a club that guarantees you access to private bathrooms.

Toilet law is a real thing

Paid toilets are common in Europe, usually charging a Euro or so for access to a clean bathroom. The Euro isn’t there to exploit; it pays for an attendant to monitor the bathroom and keep it clean, while funding additional restrooms in public places.

The US used to have 50,000 paid toilets across the country. But starting in the 1970’s, the Committee to End Pay Toilets in America — CEPTIA — organized a political campaign to make them illegal. The underlying logic for this was reasonable. There was inequality in access, with urinals sometimes being free while toilets were paid. They also weren’t perfect; the US often used annoying and inflexible coin-operated systems over Europe’s more luxe attended bathrooms.

But when the 50,000 paid toilets closed, the promised free bathrooms failed to appear in sufficient numbers. Today public bathrooms are scarce, and many of the ones that exist have a reputation for being dirty, unreliable, and in poor condition.

Paid toilet laws have been on the books for 50 years, and I don’t think we’re likely to overturn them anytime soon. New York’s law is pretty clear:

Pay toilets; prohibition. 1. On and after September first, nineteen hundred seventy-five, no owner, lessee or other occupant of any real property or any other person, copartnership or corporation shall operate or permit to be operated pay toilet facilities upon such real property.

However, I — despite famously not being a lawyer — believe I have found a loophole. In Nik-O-Lok Co. v. Carey (1976), a New York Appellate court found that:

“In our view, it is permissible to conclude that one commonly understands a "pay toilet" to mean, in its most literal sense, an immediate charge for the singular use of a closet for the discharge of human wastes.” (Emphasis mine)

SINGULAR. If it’s true that New York’s prohibition on paid bathrooms only applies to single uses, then disconnecting the payment from the use may let us recreate the paid toilet. It might look something like the Priority Pass.

A quick primer on priority pass

Airport lounges used to be a luxury product, only available to business class fliers.

That began to change with the mass availability of Priority Pass that accompanied the credit card boom of the 2010s. Holders of Priority Pass could access lesser lounges for free, as long as they were members.

The business model is pretty simple: lounges partner with groups like Priority Pass, which pay the lounge a fee per visitor. This fee goes towards food costs, maintenance, and cleaning.

For me, the number one use case for the lounge is the availability of clean bathrooms. But I don’t just need this at the airport — what if I had a Priority Pass-level bathroom anywhere I went?

The BathPass experience

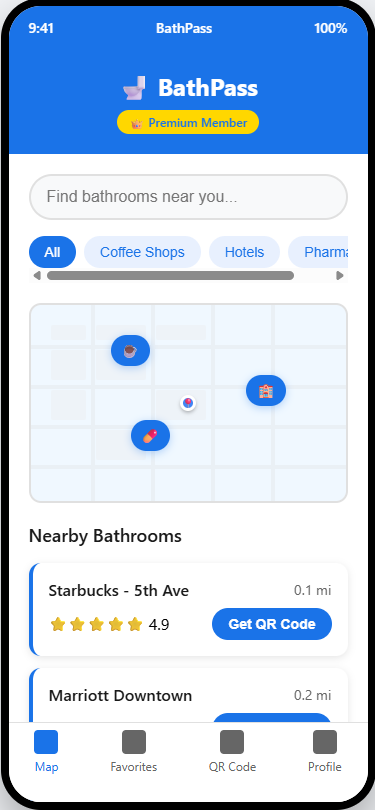

The launch experience for BathPass doesn’t need to be too complex, just a formalization of the grey market bathroom. An app shows you all of the in-network bathrooms nearby; instead of asking the Starbucks cashier for the key, you flash them a QR code showing your membership in BathPass. They give you the key, and you’re on your way.

The main difference from the Priority Pass model is that we cannot, under any circumstances, tie the price to a specific individual use of the toilet. This needs to be an all-inclusive product with unlimited usage. For that, Priority Pass charges around $40 a month or $480 a year. That’s a lot, but I literally know somebody that signed up for Equinox all access in order to have reliable bathroom access while traveling.

But you don’t need to only target people with a high willingness to pay for bathrooms. The obvious path is to partner with credit card companies. BathPass feels like a natural perk to come with Chase Sapphire or Amex Platinum cards.

It’s not just about user acquisition: BathPass will need to get bathrooms on the platform. The best suppliers overlap heavily with grey market bathrooms today: think hotel chains, coffee shops, and chain pharmacies. The bigger the better with partners; a single partnership with Marriott could seed the central business districts of every city in the world.

Because payment has to be disconnected from the usage, BathPass will need to pay a flat fee to bathrooms in the network. That’s not optimal, but I don’t see why they couldn’t pay suppliers broadly based on how many monthly visits they receive. It seems reasonable to pay different fees for establishments that have under 100 monthly visitors, 1,000-4,999 visitors, etc.

This would need to be paired with a mutual rating system. For the customer side, peeing on the seat or neglecting to flush is a fast track to 1 star ratings and a ban from the platform. But in the same way some Ubers set up chargers and mints for you, 5-star-seeking bathroom suppliers will redo their bathrooms, have regular cleanings, and always replace the toilet paper. High ratings mean more visitors and bigger reimbursements.

Expanding the market

When Uber was still growing, employees would pass out free ride codes at events around the country. The goal was to seed the markets with enough riders to reach critical mass, creating a two-sided market that could support the ecosystem they were trying to build. BathPass will need to follow the same path.

To get a sufficient customer base, BathPass would need to sign up hundreds of thousands of people across the country. There’s one clear way to get the right scale with the right buyers: partnerships. Beyond signing up everybody they can with a nice credit card, BathPass could cross-sell to Uber Gold members, chain gyms like Equinox, or fancy IBS clinics.

And like Uber’s city launchers, hordes of 20-somethings chasing the startup dream will need to roam the country convincing stores to offer their bathrooms. Early adopters could sign up at preferential rates, with word of mouth bringing in new storefronts over time.

To fund this massive growth from the cities into the suburbs, BathPass is going to need some serious venture funding. They should be able to get it.

This is legitimately a billion dollar business

Thinking a few years into BathPass, do the unit economics even potentially justify venture funding?

While the list price is $40, nearly all members would come from partnerships that reimburse at a lower level. Let’s call those $8 each, and assume that 90% of users come in at the lower rate. At 1 million members, the total revenue is $11.2M per month or $134.4M per year.

It seems reasonable that the minimum viable product needs at least 1 bathroom within a half mile of any given spot in the city — around a 10 minute walk. That would require ~50 locations in a major city; let’s call it 400 prime locations across 8 major cities in the US as a pilot.

Before making everything variable, Uber used to take a flat 30% fee from their drivers. If 30% of revenue is allocated to paying stores, that’s an average budget of $8,400 per month — or $100,800 per year — per store to join BathPass. That’s enough to get almost any coffee shop’s attention.

Scaling these assumptions, it only takes around 7.4m customers to reach a billion in revenue. If Priority Pass and LoungeKey can have 40 million combined members, that isn’t as ambitious as it sounds. Seems VC investable to me.

The complexities of scale

Much like early Uber lacked the polish it has today — upfront pricing, automatic addresses, etc. — BathPass is going to be a bit janky at first. But as BathPass evolves into a normal part of daily life, its features will evolve with it.

The obvious long-term change is the technology. The QR code system has a real limitation in requiring staff time. Why couldn’t some high-traffic locations start to add smart locks, tied to a tap from your phone? Not only does this automate the bathroom access process, it can require Face ID approval before giving access — completely eliminating account sharing.

With an opportunity to monetize grey market bathrooms, businesses would almost certainly get more strict in giving access to their toilets. Maybe some stores go BathPass only, with locks only working for members. With the “I’m ballsy enough to ask for a key without buying a $5 coffee” market closed, these users would be forced to join the network or be redirected to public bathrooms.

I’d like to think this would drive additional investment in public bathrooms around the country, but more likely would be the appearance of lower-cost alternatives. BathPass may have the finest bathrooms, but a competitor — call it EasyGo — might offer a $2 membership for emergencies.

Like the rest of the app economy, eventually this could drive a regulatory reaction. People left out of the bathroom economy will lobby to have the city crack down on BathPass. You can imagine all of the ways this could go — force BathPass to offer a free tier, tax businesses that offer BathPass, or threaten to amend the law and shut down BathPass altogether. BathPass is going to have its hands full with government relations, but that might just be the cost of doing business.

Official idea rating

5/5. I mean, hire a lawyer first to make sure it’s legal, but I 100% believe this is going to exist one day. Build it, give me advisor shares, call it the first NDI unicorn.

Bathrooms are just one example of semi-public resources that persist due to informal social norms and low usage. These types of informal privileges — bathrooms, outlets, lounging in hotel lobbies without being a guest — break down when there’s too much information sharing and organized usage. As the world’s knowledge continues to be digitized and spread, these norms will continue to break down. It’s not crazy to think that the response could be adding a price.

I don’t know what the first one of these will be, but bathrooms seem like a pretty good bet. If it’s not number one, pretty good chance that it’ll be number two.

That was a long way to go for the punchline. (And also a genuinely great idea.)

What about Priority Pass branching out and adding this to their non-lounge offerings? They already offer members discounted meals and drinks at public venues.

Slowly we will subscribe our way into the comfort of clean, public restrooms in Japan.

I read that this custom Google Map of publicly accessible toilets was the most popular 3rd party map:

https://www.got2gonyc.com/about

and NYC now launched their own map last year https://www.theverge.com/2024/6/4/24171316/nyc-public-bathroom-google-maps-view-accesibility