Creating a tariff-free coffee substitute

With coffee prices skyrocketing and tariffs adding to the pain, does it make sense to start looking locally?

If you’re a coffee drinker, you’ve probably noticed skyrocketing prices over the last year. Bulk prices are up over 21% since last August; anecdotally, the medium-nice coffee beans I used to buy at the grocery store for $16 are now pushing $25.

There are multiple intersecting reasons for the price hike. Coffee-producing regions like Brazil and Vietnam recently went through major droughts that dramatically impacted coffee production. But in the United States, prices are also responding to a new dynamic: tariffs.

Nearly 99% of coffee in the United States is imported, meaning that any disruptions to trade have an immediate and significant impact on coffee prices. Major producers like Colombia and Vietnam now face tariffs ranging from 10% to 20%, and imports from Brazil — the U.S.’ largest source of coffee until this year — are currently taxed at 50%.

Maybe the tariffs on coffee will go away — there’s a bipartisan bill proposed to repeal them — but even if they do, trade is being re-routed and coffee prices are likely to stay elevated for at least the short term. It got me thinking: could there be a tariff-free substitute?

The U.S. can’t meet its coffee needs domestically

It’s tempting to assume that the U.S. can replace its coffee imports by expanding domestic production. Sadly, there just aren’t that many places to grow coffee in the U.S.

Perhaps the most famous American coffee is Kona coffee, grown in the mountains of Hawaii. This microclimate is perfectly suited for coffee, and the beans grown there make a highly prized (and equally expensive) coffee. Unfortunately, Hawaii is pretty small — the entire area only produces about 4.3 million pounds per year, about 0.1% of the 3.5 billion pounds of coffee the U.S. consumes annually. Even tripling production wouldn’t put a dent in demand.

The other potential American coffee region is Puerto Rico, which used to produce 30 million pounds of coffee per year. That’s now a thing of the past: up to 90% of Puerto Rico’s coffee plants were destroyed in the 2017 hurricane. While the island is trying to rebuild their coffee industry, a 3-5 year growing time for new coffee plants means it’s not likely to replace imported coffee anytime soon (and given subsequent hurricanes have hindered coffee regrowth efforts, I assume financing is difficult).

And…that’s sort of it. There are micro-projects in Florida and California that are still experimental. Most of the deep south has periodic deep freezes, which would kill any large-scale attempt at growing coffee. There’s not that much we can do to expand our production of domestic coffee, outside of annexing Colombia.

So as supplies dwindle, the cost of tariffs will begin to flow to customers. But there’s a long history of people looking for substitutes when coffee becomes scarce, whether through war, blockade, or it getting really expensive. Maybe we can look to alternatives to find a way forward.

Idea 1: Barley

After the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations imposed a series of embargoes and sanctions on Italy. In response, the government began a propaganda campaign pushing self-sufficiency for key imports, including coffee beans.

The result was Caffè d’orzo, or barley coffee.

Caffè d’orzo is simply roasted barley, ground up and brewed like coffee (or, more likely for Italy, espresso). Although its popularity declined in the post-war economic boom, Caffè d’orzo is still drunk in Italy as a caffeine-free alternative.

In an affront to my 13 Italian readers, I made it as a pour over instead of the traditional Moka pot.

My initial reaction was that the raw barley smells sort of like dirt, but that largely dissipated after adding hot water. The resulting drink sure looked a lot like black coffee, and I wouldn’t necessarily have been able to tell the difference at a distance.

It wasn’t great. The flavor reminded me of the cheapest possible diner coffee, left on the heater for hours until all the flavor is lost and only the bitterness remains. Milk helps with the harshness, but the resulting drink still disappoints. Still, I can see how the bitterness and roasty flavors evokes the idea of coffee, particularly if I was being blockaded.

Idea 2: Chicory

The use of chicory as a coffee substitute likely originated in Prussia, but reached mass adoption in 19th century France. During the Napoleonic Wars, France set up the Continental System: an end to European trade with the British, which ended in mutual blockade. Unfortunately for the French, you can’t really grow coffee in Europe.

So much like the coffee-lovers of 1930s Italy, the Napoleonic French began looking for a coffee substitute. Over time, some enterprising individuals began mixing chicory in with their coffee to stretch supplies, which through the power of cultural exchange eventually became ‘New Orleans style’ coffee. Today, it’s not uncommon in some markets for chicory to be blended into cheap coffee to cut costs during times of high prices.

I also made it in a pour-over for consistency.

Much like the barley, it smells sort of bad; a cloying sweetness that I found overwhelming. It also brews a cup that looks a lot like coffee.

The taste is like a dark roast coffee with a heavy layer of licorice-like sweetness. It’s honestly not that different from New Orleans coffee, which (given New Orleans coffee is typically 40% chicory) makes me realize how overpowering the chicory is in the recipe.

But while the chicory was more appetizing than barley, both options have a critical flaw: they’re caffeine free. To me, that makes them coffee substitutes in name only. That brings us to a tariff-free source of caffeine that’s native to the U.S.: The yaupon leaf.

Idea 3: Yaupon

Yaupon is a little-acknowledged tea that’s mostly known for being North America’s only native plant containing caffeine. Yaupon was widely consumed in the U.S. for centuries, both by Native Americans across the continent and by early settlers. As the American Revolution picked up, yaupon was dubbed “liberty tea” and consumed as an alternative to the heavily taxed British imports (sound familiar?)

By the late 1700s it was popular enough that the British East India Company allegedly considered it a risk to their monopoly, lobbying for laws to ban its export to Europe. The tea largely fell out of fashion as it became associated with poverty in the 1800s, only regaining some popularity in the 2010s when pioneers across the American South began selling it at farmers markets.

There aren’t really yaupon farms at scale, so nearly all yaupon today is foraged. I got mine some from some very nice people who forage for yaupon to help protect the Houston Toad’s habitat (really).

The leaves (and twigs) smelled a bit like matcha, with a particularly strong seaweed note. Brewing it makes a clean cup of tea that’s herby and light, sort of like a milder green tea. I like it!

Maybe the marketing just got to me, but I felt a decent jolt drinking it. There’s definitely caffeine in there, along with theophylline and theobromine — which I know nothing about, but supposedly give you some extra energy as well.

Unfortunately, it’s not really a coffee substitute. The tea-like flavor fails to deliver the morning ritual I’m after. We can do better.

Combining them into a new product

Out of the 3, the barley reminded me the most of actual coffee and thus felt like the right base to start with.

Blend 1 — 60% barley, 20% chicory, 20% yaupon

The sweetness of the chicory did soften the bitterness of the barley. Unfortunately, the woodiness of the yaupon did not quite mesh with the remaining flavors:

“This tastes like compost water” — An early reviewer

Blend 2 — 60% yaupon, 20% barley, 20% chicory

A yaupon-first approach. This sort of tasted like tea with a splash of burnt coffee in it. The tea flavors were actually far too strong in the ratio — less is more with the yaupon.

Blend 3 to 5 — iterations on a chicory-first approach, leading to 71% chicory, 20% barley, 9% yaupon

The sweetness of the chicory benefitted from some of the bitterness in the barley, and smaller shares of yaupon kept the woodiness without tasting too much like tea. After several iterations, I felt like I had something decently close — and was totally wired from all of the yaupon I’d been drinking.

“If someone hadn’t had coffee in a while and was served this at a diner, they might believe that it’s actually cheap coffee” — An early reviewer

That sounds like success to me!

Could you go to market with this?

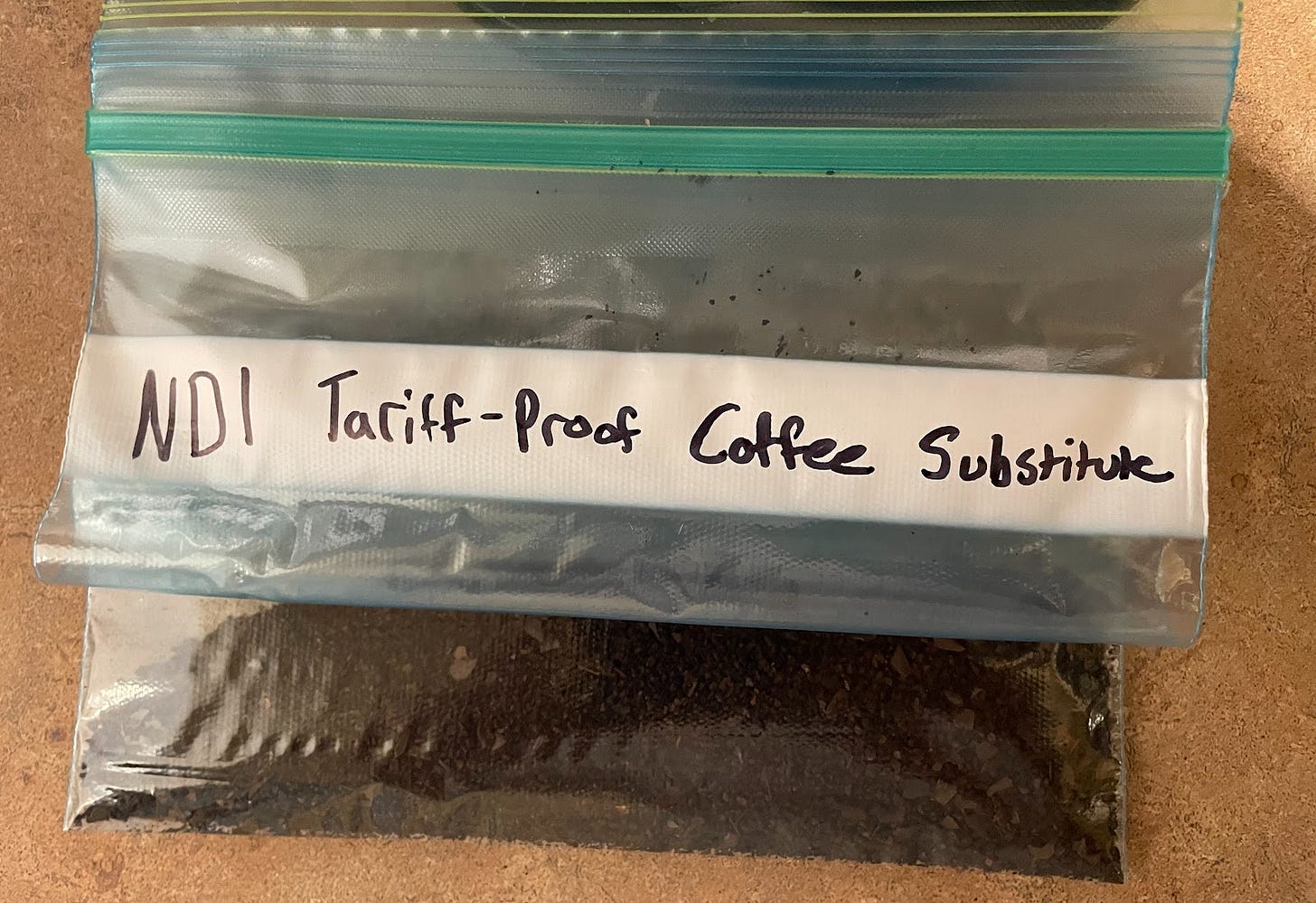

Well, first off: you tell me. If you want some NDI brew, let me know: maybe we can do a limited run batch.

My rough estimate based on wholesale prices for chicory, barley, and yaupon is that this would cost around $10.32/lb in ingredients. Add packaging, shipping, and SG&A and you’re approaching $20 per lb. So it’s going to be difficult to sell this as a cheaper coffee substitute; if it ever becomes viable, we’ve already reached crisis level in the coffee market.

One solution: find a gimmick. I’d advise an aspiring struggle-coffee entrepreneur to test three markets to see which approach gets more attention:

The tariff market: Go all-in on this being a response to tariffs. Business and finance journalists will love this as a tariff-impact story. With the media attention, promote the hell out of NDI Tariff-Proof Coffee Substitute and get on a series of podcast interviews about supply chains and responding to global market trends. Use the publicity to raise money for a better business via your new connections.

The health market: Both my barley and chicory packages are covered in (maybe dubious) boasts about how healthy they are. Yaupon also subtly does this, talking about how it provides a better stimulant than coffee with less jitters and other micro-stimulants. If coffee is expensive, the pitch — “clean caffeine that’s also good for your gut, all locally grown or foraged” — might reach audiences open to trying something new in response to expensive coffee.

People who really like American stuff: There are a lot of successful companies that boil down to being a “thing, but patriotically American” brand. A fully produced in America coffee substitute could get some legs; like the Napoleonic or Italian Fascist eras, local production in times of struggle is often a point of pride. It’s not that hard to imagine someone suffering through the mediocre NDI juice as a statement of their belief in American juche.

There’s also a fourth option: if you believe the tariffs are here to stay, become a leader in the downstream coffee industry.

Some coffee substitution might be inevitable

The combination of long lead times, uncertain tariff rates, and global shortages mean that coffee is likely to stay expensive in the U.S. for a prolonged period of time.

Coffee has evolved beyond a simple beverage into a cultural touchstone. Cafes are where people can work without an office; meeting for coffee is the casual engagement. As the price of coffee squeezes these places, owners will be stuck between declining profit margins and high prices that push out their customers.

This is an existential threat to the cafe industry. Coffee is one of the most consumed drugs in the world, but at some point people will stop buying $9 cappuccinos. Brands like Starbucks are already positioned to make this shift — expect to see more emphasis on non-coffee caffeine SKUs like refreshers or primarily milk-based drinks — but traditional “sit and work for the day” shops are in a lot of trouble.1

With elevated prices crushing margins, these shops could become real customers of coffee alternatives — not as full replacements, but as fillers to stretch coffee bean supplies a little further. Replacing 20% of coffee beans with chicory or barley meaningfully cuts costs; don’t be surprised if you see more New Orleans coffee or new, experimental coffee-herb blends on the menu at your local shop.

Of course, the transition might be a little ugly. Chicory and yaupon aren’t cultivated enough to really scale up production quickly, but DO grow all over the United States. The supply chain would start out extremely fragmented, with foragers collecting coffee substitutes to buy time while major chicory and yaupon farms get online. Foragers scaling up might begin raiding garden centers for mature yaupon trees that were previously used for decoration.

These new farming entrepreneurs will eventually seek new markets to diversify their buyers. The story of yaupon is pretty compelling; I wouldn’t be totally shocked if it became the next Yerba Mate or Kombucha, which would probably be more successful than trying to use it in fake coffee. If production really takes off, expect to see industry-funded studies and news articles on the health benefits of drinking these coffee alternatives. You’ll know we’ve made it when you can find yaupon in the supplement aisle of CVS.

The good news: coffee substitutes may save the barley industry, which is suffering from a declining craft brewing market.

Official idea rating

4/5. It tastes mediocre, but so does a lot of the coffee that Americans drink. I think it’s only a matter of time before coffee blends start actively mixing in other ingredients; Folgers will stop being 100% coffee before it reaches $20/lb.

I’m not sure an NDI brew is the future. But it only seems a matter of time before people try to create substitutes to stretch their coffee supplies and protect their wallets. It feels dramatic, but we might look back at the tariff shock as our own Continental System or wartime blockades, and new coffee substitutes as our own cultural echoes.

Maybe there’ll be enough backlash that the government finally offers a coffee exemption, like it already has for copper and coal; I actually think that’s pretty likely, given how visibly coffee prices are increasing. Until that day, we’re at increasing risk of some entrepreneur adding barley to coffee to save money and getting covered in Business Insider. When that happens, remember: you read it here first.

Including the one I write NDI at, which has pivoted heavily to serving alcohol

This article may have inspired me to buy a coffee tree, I had no idea we could grow them in South Florida. https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/trees-and-shrubs/shrubs/coffee/

“I love how he really writes as if there truly are no dumb ideas” my partner, telling the truth