Does momentum exist in prediction markets? A short analysis

A change of pace driven by a minor obsession. Back to normal NDI next week.

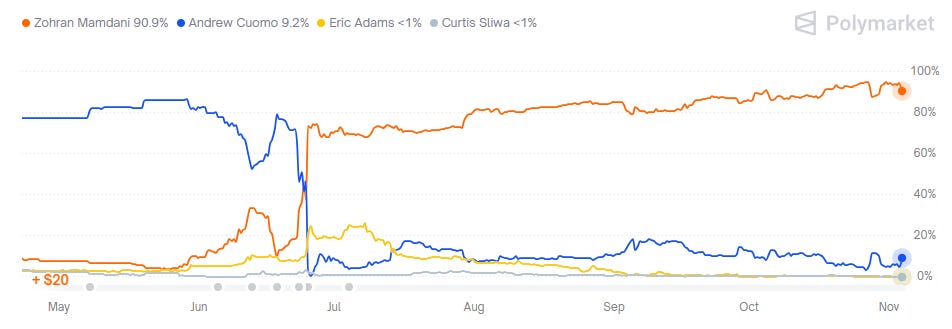

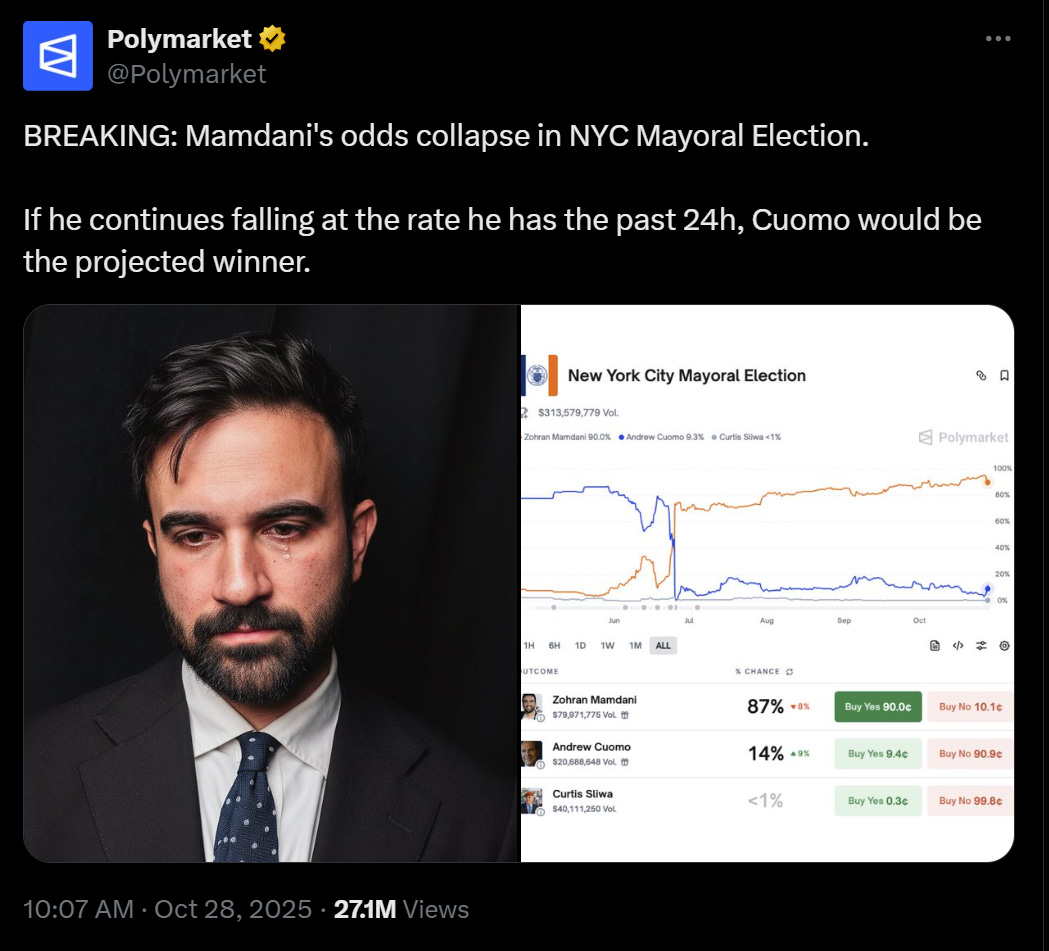

Last week, NYC mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s chance to win briefly fell from 95% to 87% on prediction markets. The official Polymarket account responded with some excellent marketing:

This is…perhaps a questionable application of prediction markets. In theory, a high liquidity market like the mayoral race (nearly $400 million in volume!1) should arbitrage out big swings that diverge from the conventional wisdom of the traders.

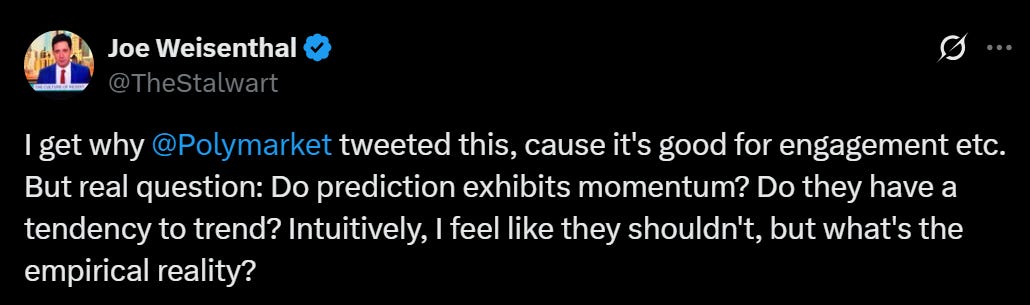

So people began asking the obvious question: does momentum exist in election prediction markets?

After two days of learning the Polymarket API, I can definitively confirm the answer is: yes, but with some caveats.

Duration makes a big difference

I looked at a set of 562 election markets that closed between 2020 and 2024 and had at least $50,000 in volume. For each of these markets, I downloaded the ending price for each day the market existed, then gave every market equal weight to avoid double-counting busy ones.2

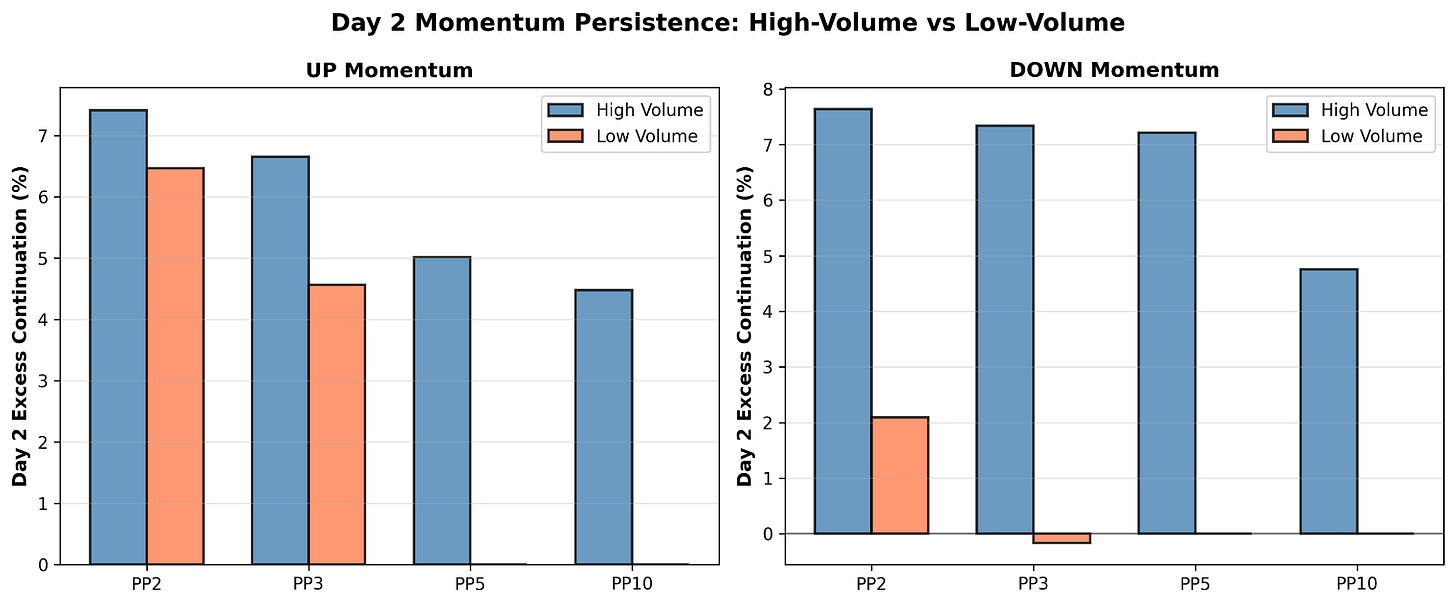

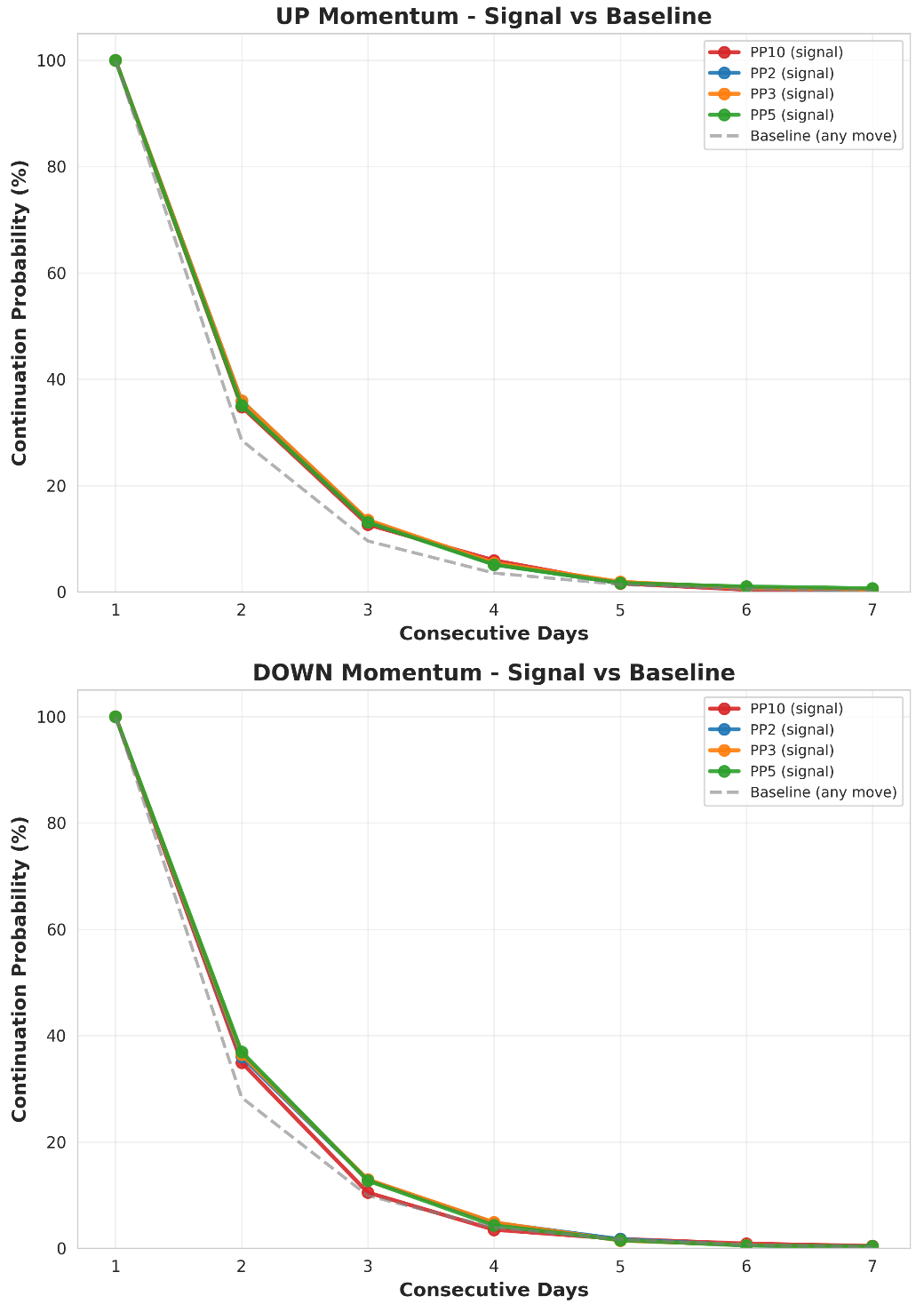

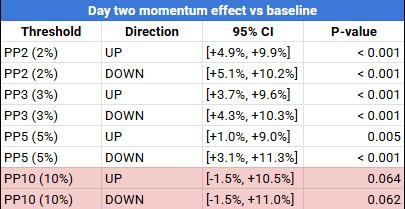

Using this data, I tried to define momentum — the probability that if there is a percentage shift at point A, that the market will keep moving any amount in the same direction the subsequent day. Surprisingly, the answer was basically the same whether the move was 2%, 3%, 5% — one day of movement correlates with a 6%-8% increased chance of moving the same direction the next day.

This effect shrinks to a 2%-3% improved chance of continuing through day 3, and fades by day 4. While momentum for down events is a little less correlated than swings up, the basic story is the same in both directions.

So momentum seems to be real, at least for a day or two. What’s interesting is that larger moves are correlated with lower odds of continuing, while smaller moves (2%-3%) have both the highest effect and the largest persistence.

You may have noticed that a 10% swing is also on the chart: surprisingly, 10% swings are less correlated to ongoing momentum. This seems unintuitive, but it actually makes sense; big enough swings likely prompts profit taking while attracting opposing bettors drawn to higher returns.

That seems to be what happened with the New York Mayoral Election, where Zohran Mamdani’s declining odds were pretty short-lived.

So why does momentum exist?

I can think of three basic theories of momentum: news-making, campaign dynamics, and momentum-trading.

Polymarket’s tweet is a good example of the news-making theory. Prediction markets have become a progressively larger part of the public eye. It’s not that uncommon to see news stories about election odds, and changes in the odds fuel narratives that impact how campaigns are reported on. If those narratives have a real-world effect on how the media reports on the race, a shift in Polymarket odds could become a self-fulfilling prophecy and even affect the outcome.

The campaign dynamics theory would say that campaigns have momentum, and prediction markets follow the campaigns. Sometimes a good debate can lead to a good poll, which can compound into new donations, volunteers, institutional support, and eventually inevitability. If prediction markets are effective in reflecting the dynamics on the ground, it might just be properly conveying information.

Finally, the momentum-trading theory would say that election markets are fun, and people like to trade in them. If people see that there’s a lot of movement in the market, it is a much more fun market to bet in. These traders are here to have a good time, and don’t have particularly good information. So when they see a change in odds, they figure someone else knows something and bet in kind.

I think it’s totally plausible that all of these play a role. Only a few very prominent markets get real attention in the press; Polymarket doesn’t tweet as much about the Barbados presidential election, so their impact would only felt in a few key markets. Campaigns certainly believe in momentum, and it’s true that good news begets good news in an election (and vice-versa!). The Big Mo is a cliche for a reason.

In theory, well-capitalized markets should wipe out momentum traders. But what about in not-well capitalized markets? If you flip our filter and only look at markets below $50k in volume, you find that large swings (5%+) have virtually no impact on moves for day two. Maybe that’s because low volume means everything is swingier, but it could point to momentum traders having some role amplifying moves in larger markets. Maybe momentum traders are less up to date on Uruguayan politics than who will win Pennsylvania.

The biggest question: does momentum tell us the winner?

If you’re reading a tweet from Polymarket, odds are you’re interested in divining something about the outcome of the race. For New York Mayor, I’d recommend waiting 12 hours to find out.

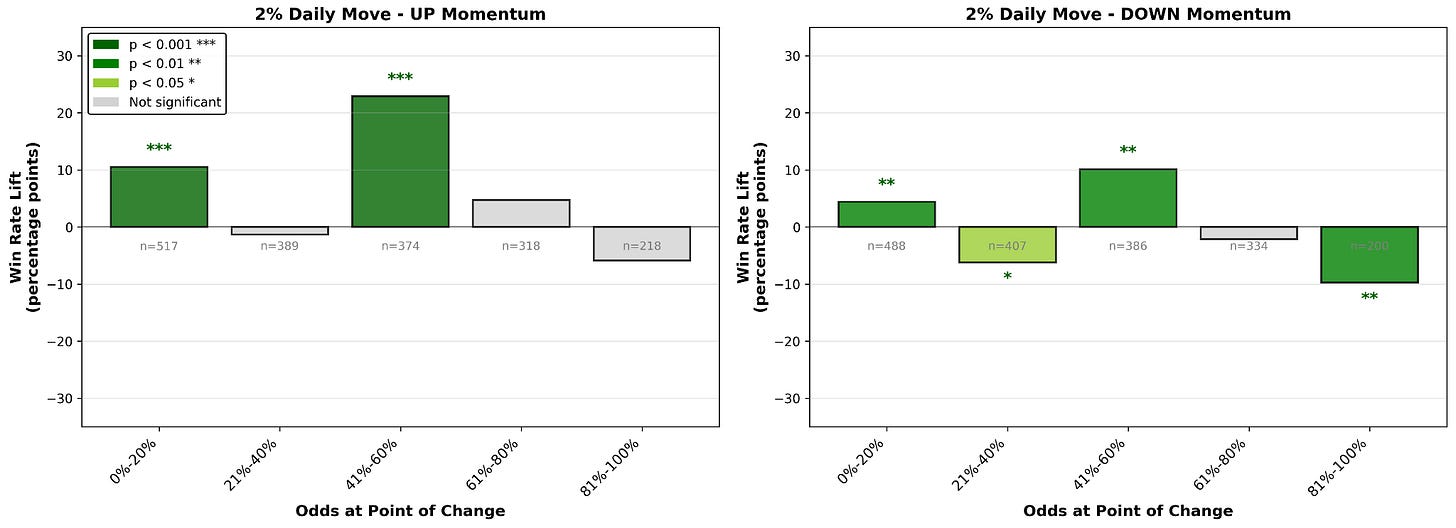

But since you asked, it turns out that large single-day swings in odds do correlate with the final outcome. I ran a second analysis that checked: for each swing of X at a given odds to win, how often did that token resolve yes:

In other words, a 2% daily move down for someone with 81%+ odds is correlated with a 10% higher chance of the market resolving no. The biggest effects for 2% jumps are long shots (<20%) and for mid-range (40%-60%). I can see why this happens, given that these are likely the spaces where you see real information getting priced in (either a 50/50 race or a total long shot candidate getting some momentum).

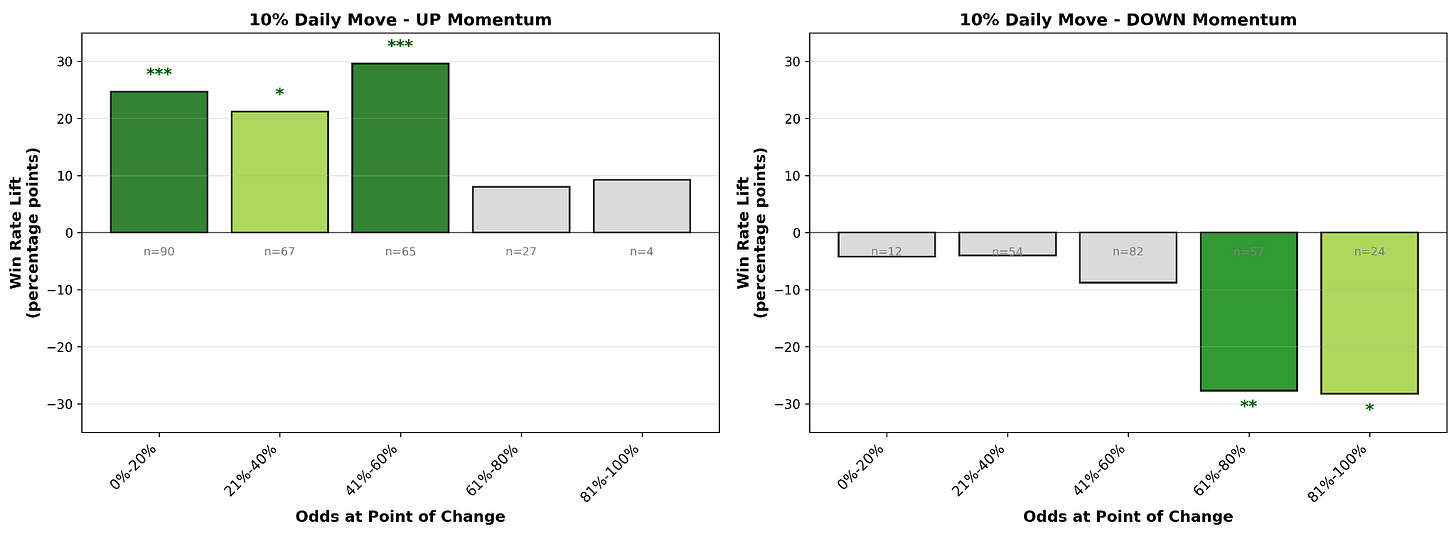

But the real question: does Zohran’s 10% swing down mean anything?

It turns out that while 10% swings aren’t as predictive of momentum, they are correlated with outcome. A 10% swing UP at odds <=60% has a statistically significant increased chance of resolving yes (over 20% higher!). A 10% swing DOWN at 61% or above is statistically significantly more likely to resolve no about 25% more often.

This makes sense to me. When the odds are very skewed in one direction or the other, the winner has almost become conventional wisdom. If something shifts those markets 10%+, it probably means that real new information has come to light. I’d imagine most drops this large are in response to a “major poll came out/disastrous debate” level of impact.

So: is Zohran cooked? If he is, it’s probably not because of the swing in the prediction market. No real new information came out, and his odds returned to 93% two days later.

I don’t have a lot of examples of favorites that dropped 10% only to recover. But of the 20 that recovered at least 5%, 90% went on to win. It’s not proof, but I certainly wouldn’t take out a loan to make a bet against him on Polymarket.

Conclusion:

As someone who occasionally writes about prediction markets, this was both fun and extremely time consuming to analyze.

One day I’d like to see how well this holds in other types of markets. Well-capitalized prediction markets for sports, cryptocurrency, financial, policy, and more might have totally different dynamics. That said, even elections are a little suspect: I’m not sure “Who will win Georgia in 2024” has the same market dynamics or bettors as “Who will be the next prime minister of Iceland,” and maybe it’s not fair to blend the two.

So we’ll see how the New York election goes tomorrow. If the Polymarket tweet wasn’t right in the end, it at least sparked some interesting research — and given it got over 25 million views, I’m sure their social media person will continue to give us frequent updates on the state of the race.

At the time of writing

There are some biases in the way I approached this. Because I’m using midnight UTC cutoffs, I’m losing all of the intraday trading momentum which may or may not exist. We also have far fewer large moves in this period, so the results for 10% jumps or drops are directional. All of this is association, not causal.

Also considering I got a B+ in stats 13 years ago, do not trade on this.

In political campaigns, momentum also exists as an underlying phenomenon reflecting the gradual shift in public opinion. If a candidate picks up significant new support, it tends to take time for word of mouth, media to work. Polls definitely exhibit momentum. I'm not surprised there's a bit of that in prediction markets! Market efficiency means there's probably less momentum than polling alone, but the prices still have to track with polling (ie. impossible to know when a trend stops so the fair value is not obvious).

One reason you might see momentum is if no news is good news.

Consider a market on "will there be an earthquake above [magnitude] in [region] before [date]"

Every day that goes by without an earthquake, the probability drops slightly.

But occasionally, there will be a big quake, and the probability will jump to 1. Or there will be small tremors that could indicate a quake is coming. And the probability will jump upwards.

For politics, this might be "the only way this candidate loses is if there is a giant scandal, so each scandal free day is good news".

If this is what is happening, then momentum traders won't win or lose on average. Usually they will make a small win. Occasionally they will make a huge loss.