The 1924 New Mexico regional banking panic

A change in tone for Labor Day Weekend: let's revisit a century-old banking panic. Back to normal programming next week

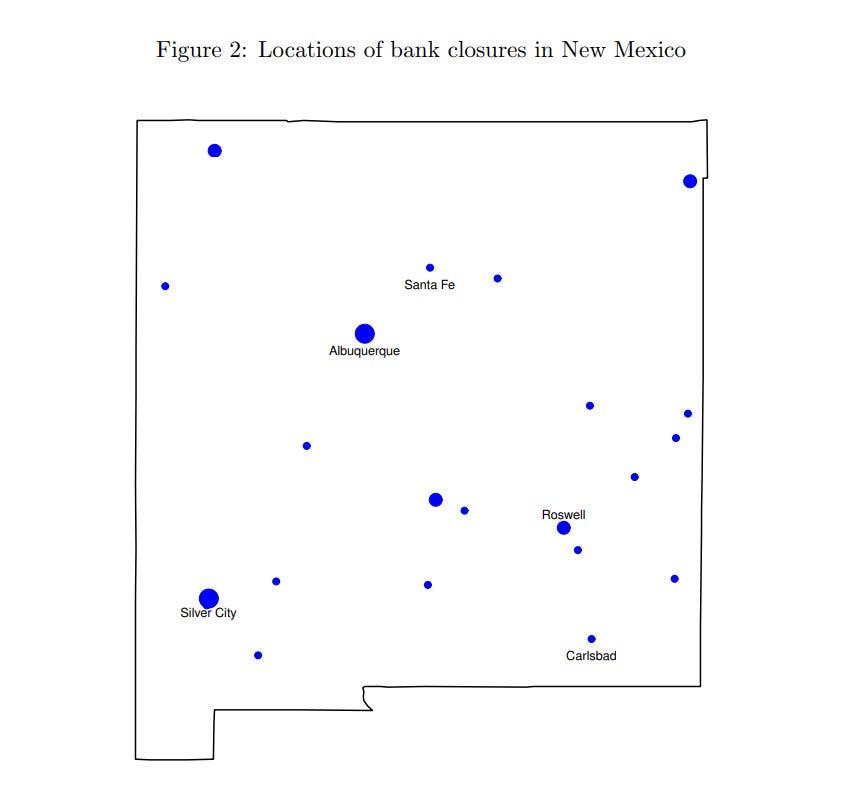

Remember when Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapsed a few years ago?

The quick version of the story is that SVB got a lot of deposits from the tech industry as the standard bank for startups. They grew especially quickly during the post-COVID low-interest-rate venture capital boom of 2020-2022.

With lots of deposits and low interest rates, SVB decided to seek a little extra margin by buying long-dated bonds. Inflation hit, interest rates rose from 0.25% to 4.75% over the course of a year, and suddenly SVB had a lot of underwater instruments that couldn’t quickly be converted to cash.

The problem was that they had a lot of uninsured deposits above the FDIC limit of $250,000, very concentrated in a close-knit industry. Rumors kicked off that SVB was short on cash, VCs told their portfolio companies to pull their money out, and in a few hours there were over $40 billion of withdrawals.

This raised the specter of a bank contagion — a failure at SVB causing runs on other banks, SVB customers unable to pay their bills, and a broad-based economic and banking collapse. The Fed, Treasury, and FDIC came out with shock and awe, guaranteeing all deposits at SVB. Things calmed down, SVB was acquired by First Citizens, and a lot of risk managers at banks had a terrible few weeks.

This was my first experience of a widely-followed bank run — before then, they were something that happened in collapsing economies or as a bit of interesting economic history. So when the Fed released a great article on The Banking Panic in New Mexico in 1924, I couldn’t help but be interested in the parallels.

So this week, let’s skip the business idea and do a bit of economic history.

The early 20th century economy of New Mexico

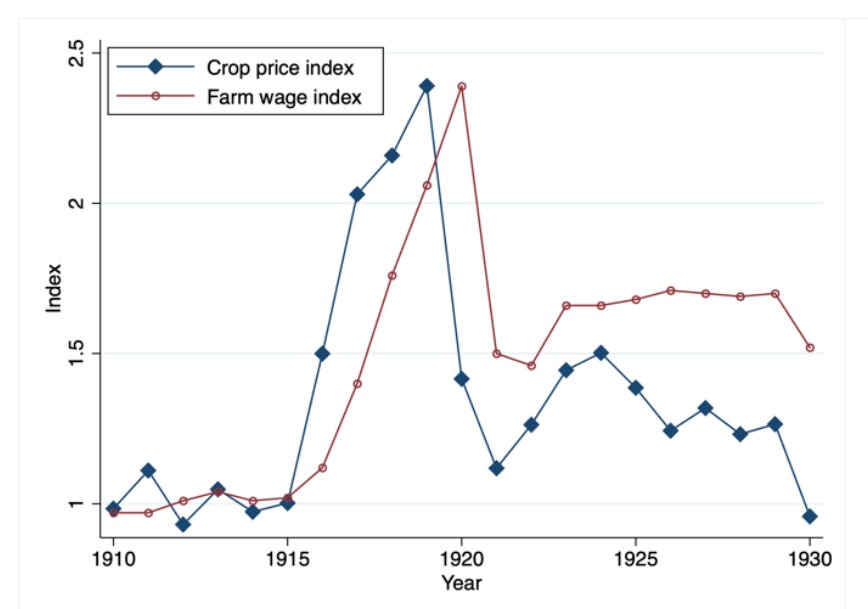

The First World War created a massive supply shock for European agriculture. Production for staples like wheat fell by 50%+ in France, Germany, and Italy, while Livestock collapsed by 75%+ in places like Denmark.1 This created an opportunity for American farmers, who took advantage of the soaring agricultural prices to expand production and export to Europe.

New Mexico was a major producer of cattle and sheep in this period. In response to the demand, farmers sought loans from local banks to expand operations based on inflated wartime prices. The financial system responded to this spike in demand, with a rush of new banks opening to serve demand for credit.

These highly leveraged cattle farmers took a double hit in the 1920s. As European production recovered post-war, the price of agricultural commodities collapsed more than 50%; cattle collapsed from $16 per hundred pounds in 1919 to $7 per hundred pounds in 1922 (albeit still above the prewar average). At the same time, New Mexico suffered a major drought that was hugely damaging to agriculture.

This was a bad situation for the local banking system, which had an estimated 70% of outstanding loans in agriculture (typically using cattle or crops for collateral). Like SVB’s long-dated bonds, these were fairly illiquid, meaning that in the case of a bank run it was difficult to turn them into cash.

Worse, many of these banks were chartered by the state — which had lower capital requirements — meaning they were not required to join the Federal Reserve system. Only about half of the banks in New Mexico opted to affiliate with the Fed; the other half had no access to a lender of last resort.

The panic and the response

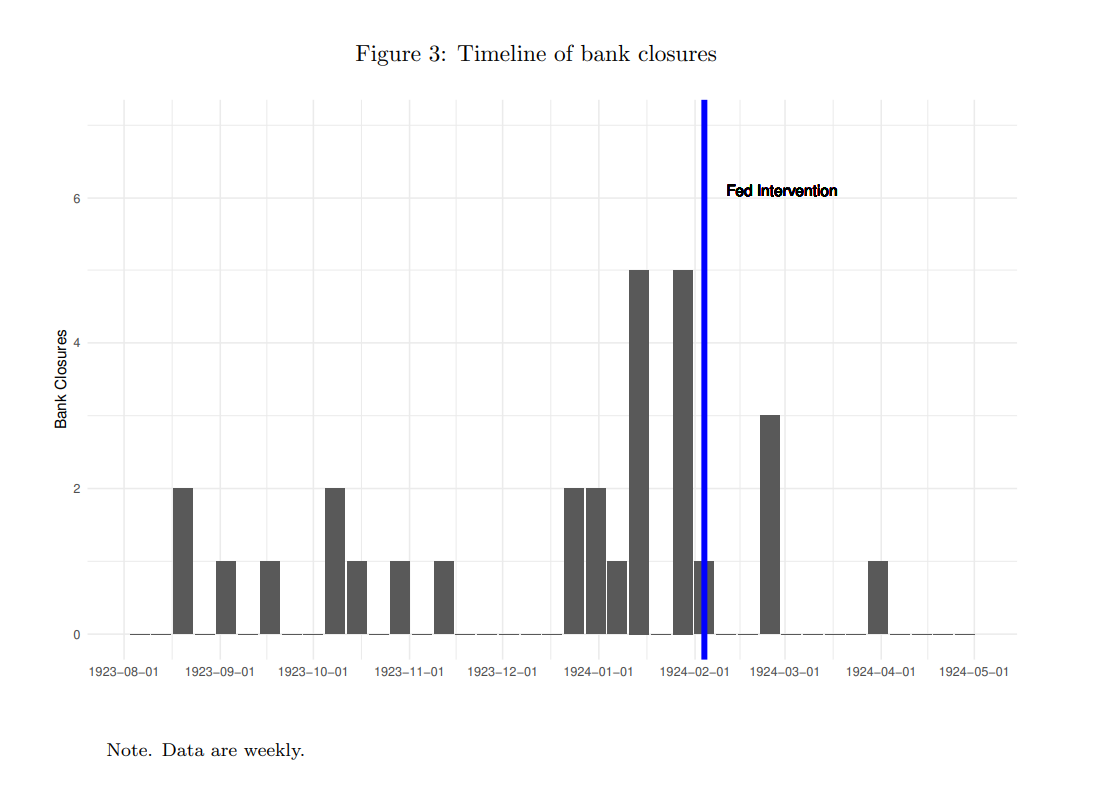

New Mexican banks began closing in early 1923, accelerating throughout the course of the year. The crisis hit a peak in January 1924, when 13 banks closed in a single month. You can imagine the panic for locals, some of who saw every bank in their city close in a single day.

Interestingly, Carlson doesn’t find that the banks that closed were in particularly worse health than banks that remained open. The main driver was liquidity; banks with more liquid assets tended to survive, while those with less liquidity were more likely to close. It’s a very classic bank run story: the panic and rush to withdraw money is what causes the crisis, and liquidity is what lets a bank survive it (or not).

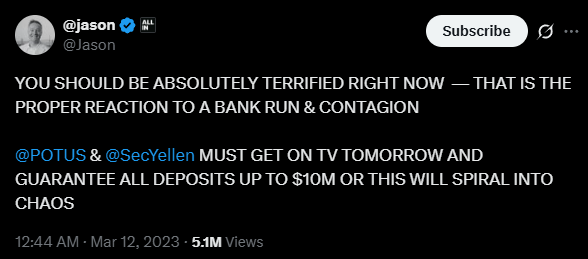

The generally larger Albuquerque banks held some deposits from regional banks around the state. Like SVB, there was fear that cross-bank relationships could act as a contagion. By February, three of the five banks in Albuquerque had closed down, accelerating the run on the final two banks. The two remaining banks were flooded with anxious depositors, who withdrew nearly 5% of total deposits in a single day.

The Fed arrives

The Fed responded with maximum spectacle. Borrowing a plane from the nearby Fort Bliss Army base, the El Paso branch of the Fed began to airlift $500,000 in cash to support local banks. From Carlson:

“The Albuquerque Journal (1924) describes the scene as follows: “The crowd in the bank [the First National] lobby gave a cheer when, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, Chief of Police Galusha and Sheriff Felipe Zamora, with a squad of policemen and deputies sheriffs armed with shotguns cleared a path through which two army officers walked, carrying sacks containing $500,000 in currency. The army men had flown from El Paso in an airplane, bringing the money in the record time of two hours.'“ — The Banking Panic in New Mexico in 1924 and the Response of the Federal Reserve

A quick aside: The airlifted cash coming in with huge spectacle is a time-tested method to restore confidence. In 2002, Uruguay had a massive currency crisis where the U.S. Treasury gave a $1.5 billion dollar bridge loan until the IMF could distribute cash. While most of it arrived electronically, rumors spread of an “avión del dinero” — a money plane — carrying huge amounts of cash. While it didn’t carry $1.5 billion, there really was a plane bringing cash to support Uruguayan banks.

A big deal was made of waiting for the money plane to arrive, which ended up being psychologically impactful — people waited until they saw the plane arrive on TV before they went to the bank, knowing it would have money. Uruguay paid the U.S. back four days later, but the spectacle was a meaningful (and memorable) part of resolving the crisis.

Reports surfaced that the Fed had already sent another $500,000, with a million more ready to go if needed. Statements came out that the treasury, Fed, and War Finance Corporation were ready to step in to calm the situation. These strong statements of support began to restore confidence in the banking system.

More quietly, the Fed lent additional money through the discount window to a small number of especially distressed banks through 1924. There was no public reporting that these banks were particularly distressed, which likely helped avoid a further run on their deposits.

Both of these actions served to indirectly rescue the state-chartered banks in their time of crisis. The federal banks were able to access capital through the discount window,2 shoring up the risk to the state-chartered banks they had relationships with and allowed liquidity to spill over outside of the direct federal system. At the same time, the level of public support reduced the run on the banks everywhere — not just the covered institutions.

At the end of the crisis, confidence was broadly restored. Some of the closed banks were even able to find new equity investors that allowed them to reopen, including in smaller locales like Silver City.

Why care about the 1924 crisis?

So this Labor Day, why am I writing about a hundred year old banking crisis?

Some of it is just that I enjoyed the paper. Economic history has the effect of making you think about the second order effects of big events. I know a decent amount about the First World War; I had never thought about how shipping all of the men to fight meant that agricultural output declined. I’d heard that the US lent a lot of money to the Entente; I hadn’t fully processed that it was partially to buy American food, not just sending weapons.

But history can also feel weirdly familiar; I kept thinking back to SVB while reading this article. The progression of the crisis really is the same general story we see over and over again with financial crises — panic, spillover into adjacent systems, and response.

One of the subplots of the New Mexico banking crisis was the impact of state bank failures on federally regulated banks. Intervention to stabilize the federal banks implicitly shored up the non-federal part of the system. There was a similar subplot with SVB — the risk of failing stablecoins.3

At the height of the SVB crisis, Circle — which runs the stablecoin USDC — announced that they had over $3 billion in deposits at SVB they couldn’t get out. A panic ran on USDC and it depegged from $1 per coin to as low as $0.88 per dollar. In the same way that state banks got liquidity indirectly through Federal intervention, the peg only recovered when SVB was able to get their bailout; if SVB had failed more completely, it could have caused a cascading reaction that further disrupted the crypto market.

It’s not quite right to call Decentralized Finance (DeFi) lending analogous to the state-chartered banks…but it’s a little similar? The Fed, by definition, does not directly regulate DeFi institutions. It’s a growing source of parallel financial services, intertwined with the banking system but not part of it. It’s not so hard to imagine another traditional bank failure putting pressure on the crypto market.

With the GENIUS Act giving regulatory guidance for stablecoins, DeFi networks are likely to grow and get more embedded with the broader financial system. Some banks are even beginning to explore the idea of collateralizing loans with crypto; as the two sectors get more intertwined, cross-contagion risk seems like it’s destined to become a topic of conversation. If a banking crisis hits both markets at once, the Fed might find itself looking back to an old western banking panic as they plan their response.

Credit to: Carlson, Mark (2025). “The Banking Panic in New Mexico in 1924 and the Response of the Federal Reserve,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2025-064. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2025.064.

I also thought it was weird that Denmark — which was neutral — had a livestock collapse. It’s because they got stuck between the British blockade of Germany and unrestricted submarine warfare; Denmark relied on importing feed for animals, so as trade collapsed from the war herds were culled and production plummeted.

The discount window, very simply, is the Fed’s facility for short-term collateralized loans to depository institutions like banks or credit unions. Or more simply, the Fed gives banks loans against safe assets on their books to help with liquidity crunches.

Stablecoins are, very simply, crypto tokens that aim to maintain a 1:1 peg with the dollar, either through fiat backing (holding dollars or treasury bonds), crypto backing (holding other cryptocurrencies), or algorithmic rule-setting (it’s complicated).

I enjoyed the change of pace today (but look forward to the next NDI).

This was super interesting, but I am a sucker for Economic History.