The big idea: A job you can buy and sell

Finding a job is hard enough. What if you had to buy your next role?

Dockworkers across the United States organized a major strike last year, threatening to halt operations at key American ports. During the strikes I saw a claim that these dockworker jobs are essentially hereditary, passed down generation to generation via union hiring practices.

I haven’t been able to find clear evidence one way or the other on whether this is actually true, despite some scattered stories. But the idea reminded me of medieval guilds — professional associations that controlled who was allowed to do most forms of skilled labor. Some of this was hereditary; your last name was Shoemaker, and you were born to make shoes.1

It’s how things (and people) worked for centuries; why not today? Could we develop an inheritable job?

This sort of exists today

Most European cities had some kind of guild system until the late 1700s. Essentially, a group of people with the same job got together and agreed to set standards, maintain quality, and limit who could work in the industry. So if you were a watchmaker, you had to join the watchmaker guild.

Getting in wasn’t easy; you’d have to apprentice, buy your way in, inherit the right to join, or some combination of the above. If you tried making a watch outside the guild, you’d face punishment ranging from the city shutting you down to someone from the guild beating you up.

It sounds pretty alien, but also… kind of familiar? State bar associations are effectively a guild for lawyers — they set standards for admission and punish members who break professional rules. The American Medical Association (AMA) is sort of a guild for medical practitioners, lobbying to limit residency slots to control the number of doctors. Taxi medallions2 are capped, with many cities require years of training to start driving. But outside of the medallions, these roles are only inheritable in the sense that your lawyer parents probably want you to go to law school.3

The big obstacle is that there just aren’t that many industries where you can prevent outside entry — and without that, guilds fall apart. When Uber came in, the taxi cartels didn’t survive. You might be able to control who gets limited jobs at a fire department, but you’re not going to have much success controlling who becomes a graphic designer. And while I think we’ll see increasing efforts to protect certain jobs as AI advances, creating guilds for every type of worker probably isn’t realistic.

But I’m not ready to give up on this idea. If you can’t inherit a job, maybe you can buy and sell one instead.

A job is more than a paycheck (it’s an asset)

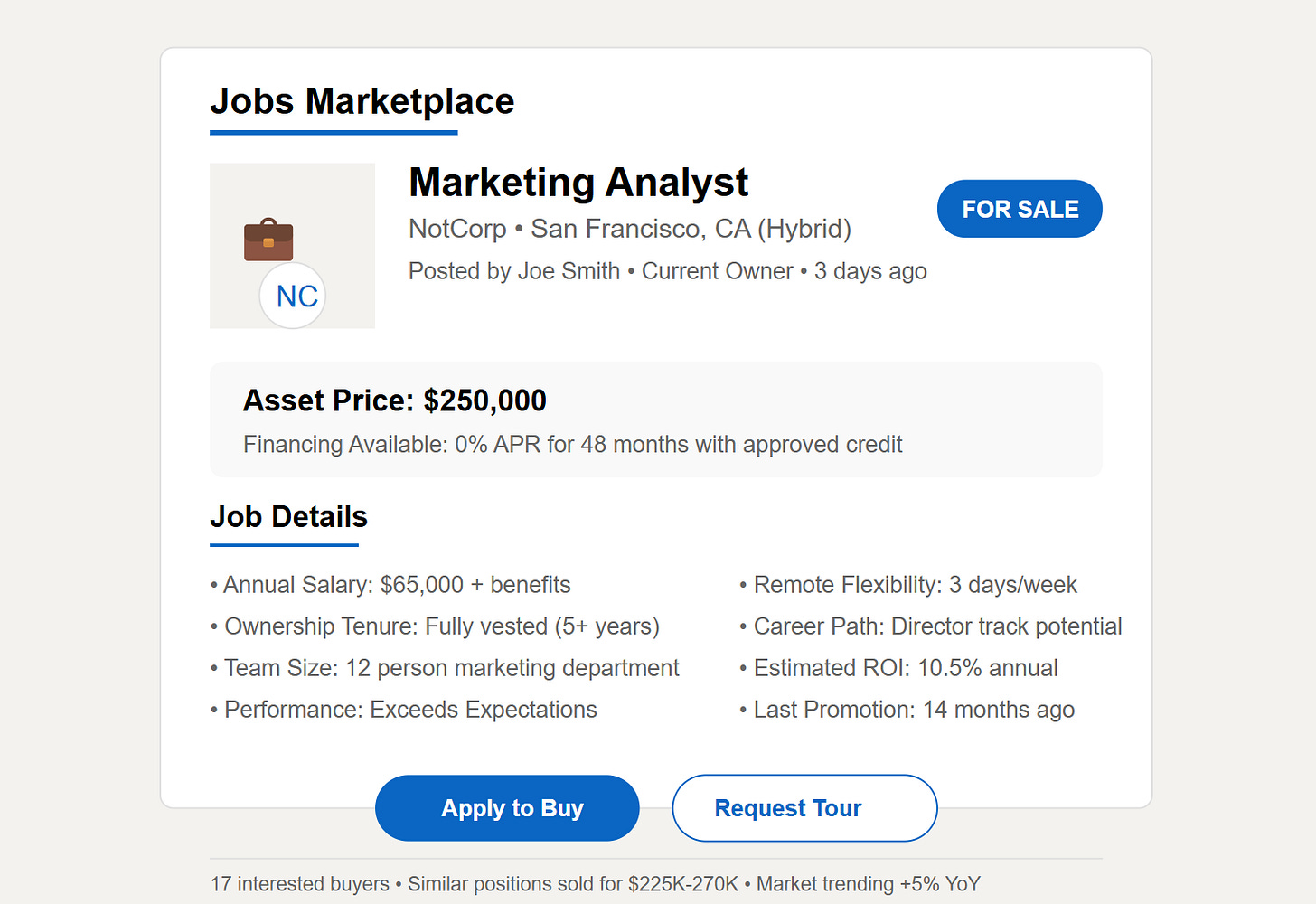

Today, any equity you get from your job is given in the form of company stock. But what if your actual job was the asset? Ownership of the job might vest over time (say, 5 years), and when you leave you could sell your role for a market price — or your company can buy it back at fair market value. It’s not that different from an equity buy-in for a law firm.4

Now, you might be thinking — if reinstating guilds is hard, giving a departing employee control over who takes over their role at a company is impossible. But for the right company…maybe this isn’t as crazy as it sounds? There could be some benefits to giving employees ownership of their jobs.

Retention: if it takes 5 years to fully vest job ownership, employees will want to stay. Expect dramatically reduced voluntary attrition for eligible employees.

Talent attraction: the best employees might seek out this kind of ownership. It’s a strong signal for hiring that someone thinks they can last 5 years to ownership.

Continuity: today, the primary reason to go above and beyond with documenting how you do your job is a sense of obligation. Departing employees will be financially aligned to provide a good transition to new hires.

So what does it mean to own your job? It would have to include a series of rights and responsibilities, such as:

You can work your job as well as sell, rent, or loan it to others that meet minimum standards

If your job is lost (via layoffs, etc) the employer would need to buy your equity at the fair market value (although maybe there’s a “burned down the office” clause to handle misconduct).

You must disclose known issues with the role when selling (like a house inspection).

Employers get the right of first refusal — they can buy back the job at market rate before external sale.

It sounds radical, but it might not be as bad for the company as it seems? Sure, if you’re laid off a company would have to pay out your vested ownership — is that so different from severance? Companies spend millions on talent acquisition; for the right industries, outsourcing it to departing employees could be brilliant. The biggest obstacle is less control in who owns the job on sale, but that can be solved by requiring company approval of potential buyers. If a company really wanted to do this you could squint and see it working.

The world of an owned job

With that structure in place, things start to look pretty weird.

Imagine you’re starting your career. You could go to a job board and apply to your first job. But companies tend to keep a pretty consistent number of entry-level jobs; firsthand opportunities would be rare. So your first stop is probably the private job market, purchasing an entry level job from someone that’s starting to move into their mid-career.

The price of a job would probably be pretty high. To make it as simple as possible, let’s assume interest rates are similar to a mortgage (maybe buying a job isn’t that different from buying an investment property?). The fair market value of a perpetual $60,000 per year bond at a 6% interest rate would be 60,000/6%, or $1 million dollars.

Of course, the real price would be shaped by other factors — off the top of my head, there’s taxes (payroll, etc), having to work 40-ish hours per week, career advancement, speculative value, and how interesting the job is. But even at 25% of perpetuity value, most people are going to need a loan to buy a job. This process probably looks a lot like getting a mortgage — but instead of validating income, they’re going to want to validate your educational and employment history.

Where do you find a job to buy? LinkedIn would probably have a marketplace, but the best jobs would mostly be sold in private markets. Why? The quality of the candidate matters to maintain the value of the job long-term; lenders financing the purchase of a job will want to validate that candidates are a good credit risk.

Maybe recruiters will become something like apartment brokers in NYC — validating the quality of applicants and acting as gatekeepers that demand 15% of the yearly salary to even submit an application. And much like apartments in New York, you might start to see bidding wars for the best jobs that drive up their price dramatically.

So you find a job, get financing, and go through what is presumably an invasive approval process before the company signs off on your purchase. Culturally, it’s going to be weird. Does a stigma develop against people who bought their job vs earning it firsthand? Your job is now an asset; does getting put on a PIP reduce the equity value of the job? Can you accidentally get underwater on your loan and trigger job repossession if the company starts doing poorly? Is there insurance for that?

A bigger issue is that this would reinforce every inequality you can imagine. Job seekers with assets would have an easier time getting loans to buy expensive jobs. Parents would leave their jobs to their kids in their will. Lending standards might subtly (or not subtly) reinforce class differences. It’s a pretty grim setup for a first generation grad.

But for incumbent owners, it might be pretty sweet

One of the implicit dynamics of this system is that there’s an incumbency advantage. As more jobs vest, there’s more supply and less impetus for companies to create new ones. So, much like housing, as time goes on people with job ownership would see the value skyrocket while the newer generation finds it hard to get onto the ladder. NIMBYism for jobs will see the economy burn down before a single additional job is created in your field.

For job owners, work becomes significantly more flexible. Want to take a sabbatical or try a new job out? Rent out your existing one while you go see if you have what it takes to be a musician. If you want to move on, you can hold onto your job until you secure something new.

Owning a job gives a lot of financial flexibility too. You can imagine job equity loans and home equity loans as two sides of the same coin, leveraging one asset to buy the other. The asset flywheel would propel some people — a good job lets them get a good house, which lets them get equity loans to do a bunch of investments, which creates enough money to buy a CEO job. Working your way up the corporate ladder becomes an exercise in wealth building.

Corporate life changes too

As a larger share of jobs are owned by employees, some interesting dynamics emerge.

On the individual side, you can imagine job flippers playing the role of house flipper today. Buy into a role, spruce up the job responsibilities, get a promotion or two, then flip it for a 2x-3x multiple. Arbitrage opportunities would be everywhere for a highly qualified worker, and it’d make employee planning truly nightmarish for firms.

Today, despite any negative consequences, layoffs net save money for a company. But supply and demand would apply to jobs; if a company lays off 75% of their marketing team, the supply/demand mismatch will drive up the value of the remaining positions. That means higher payouts if the company wants to buy those jobs back, and higher equity values for future hires. The end result is that companies would be slower to hire and fire.

There are also some weird counter-cyclical incentives; in boom times with abundant jobs, the value of a new job would go down. Companies with bloated departments would take advantage of lower buyout costs, cutting jobs in response to the abundance of other opportunities (is this better or worse timing for the people laid off?) Conversely, in bad economies the equity value of a job would skyrocket. That means that getting a job in a recession becomes expensive — but you could see a jump in early retirements as job holders take advantage of inflated asset prices. Pretty weird!

There’s a lot of strange places this could go. Is a loan for a job sort of a replacement for a four-year degree, down to taking student/job equity loans? You can imagine the creation of pseudo ”scholarships” to help promising young people get their first role. Corporate benefits would change; is there an HSA equivalent to help save for purchasing your next jobs? Will companies offer better loan terms as part of a promotion package? And do activist employees start pushing for layoffs on their own team before quitting as a way to inflate their equity value?

Of course, all of this takes the optimistic view that each person will only have one job. But the opportunity here is pretty obvious — raise a fund, buy a bunch of jobs, and rent them out. All of the panic over private equity buying housing would be 100 times worse as PE buys up every opportunity to get a job in tech as landlords for labor. In the end, it sort of just looks like big companies taking a cut of everybody’s salary.

Is there really a chance this could work?

I don’t think the legal, cultural, or regulatory structure exists today to make something like this a reality — and I’m not sure it would be wise even if there was.

But our relationship with jobs will probably shift as AI becomes a bigger part of working life. We’re probably heading towards a future where it’ll take less to get up to speed on a new job — AI can catch you up on institutional knowledge, and upskilling becomes easier with a conversational assistant.

In that world, relationships might become more important than who actually does the work. That means less security for white collar workers, even assuming the number of jobs doesn’t change much. Converting a job into an asset might be a way to lock in that value in a time of insecurity.

During times of economic disruption we’ve historically seen efforts to preserve the working status quo — guilds, luddites, unions, and licensing orgs. I don’t know if jobs as an asset is the answer, but there will absolutely be new economic structures developed to ease the disruption. Hopefully whatever we come up with has better incentives.

Official idea rating

1.2/5. While I would love to be part of the job aristocracy of early beneficiaries of this system, I think this would be net bad for society. I barely touched on the political economy around all this, but politics would probably reshape around protecting incumbent job-owners vs. opening opportunity for renters. So maybe it’s good that we’re not seeing work HOAs sending letters to protect their job equity value. But if everything is going to be financialized and turned into an asset, I’d bet your job is higher on the list than you’d expect.

By one count, about 30-35% of all English speakers have a surname that was derived from an occupation at some point, from the obvious (Smith, Mason, Tailor), to the more esoteric (Ackermann is Old English for ‘plowman,’ and Kellogg is literally ‘kill hog,’ ie. a pig slaughterer).

A transferable permit that gives the owner the legal right to operate a taxi in a specific city. Maybe the closest thing to the vision of this article.

Not to say that there isn’t nepotism in the world — it helps to be a Kennedy if you want to get into politics. But that’s not quite the same as an inherited job

Traditional law firms have you “buy-in” when you reach partner. This money is used to buy ownership in the firm; partners who leave can sell their equity back to the firm or to incoming partners

Came into this post thinking about how monumentally dumb this idea was. Your arguments made it less dumb. There’s a chance, albeit small, that this works. Your mind is beautiful, thanks for sharing.

I don't know how you think of this stuff every week but I love it