The big idea: Marriage-backed bonds

For many couples, getting married means a guaranteed tax break. Why can't they use it to pay for their wedding?

Weddings have gotten really, really expensive. Some sources say that the cost of a wedding has reached $33,000 on average, driven by higher food and beverage costs, venue fees, and bigger guest lists.

In response, some couples are going into debt. Roughly two-thirds of surveyed newlyweds took out a loan to pay for their wedding. A growing wedding finance industry — an $11B global market today — targets newlyweds with high interest rate loans topped with origination fees up to 12%. A big wedding is a lot of fun, but the financial hit starts many lovebirds’ new life off on the wrong foot.

At the same time, marriage is the beginning of at least one financial boon: the ability to file taxes jointly. For couples with earnings gaps, this can easily reach thousands of dollars in tax savings per year. What if you could securitize those tax benefits to fund your wedding?

The US tax system benefits unequal earners

Federal taxes in the US work on a progressive taxation system, with higher tax rates for earned income above different thresholds. For married couples filing jointly, the thresholds for each tax bracket doubles1; if a tax rate previously came in at $100,525, now it comes in at $201,050.

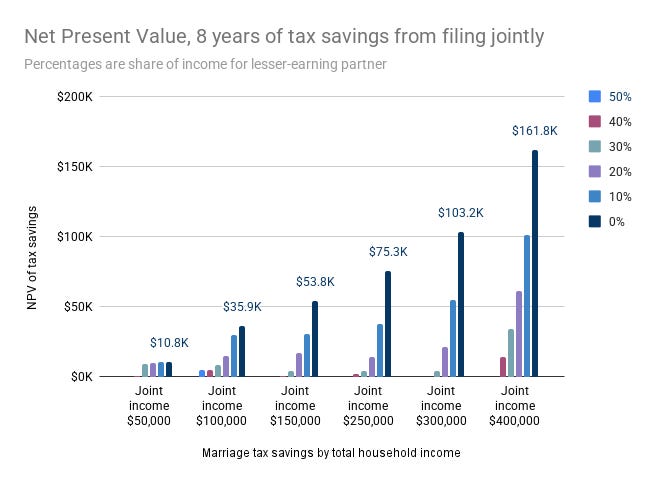

If both spouses make around the same amount, the doubled brackets don’t change anything. But if one spouse makes much more, they can “use” their partner's lower bracket and standard deduction; a couple earning $150,000 from a single earner saves over $9,000 per year from getting married.

This is real money over the course of a marriage, but it’s not flexible: either your take home pay goes up a little, or you have to wait for your big refund. There are dozens of cottage industries like legal finance that let you pull future money out early. Why should tax savings be different?

Introducing: the marriage bond

Imagine a couple looking to pay for a $33,000 wedding. Instead of taking out debt or asking their parents for money, they sign up for a Marriage-Backed Bond (MBB). The MBB works pretty simply:

For the duration of the bond, the couple calculates their taxes as if they filed separately

They calculate what they actually owe jointly

The difference — or “marriage surplus” — is paid out to bondholders.

It’s a love-powered coupon stream: semi-predictable, recurring, and guaranteed until the note matures or the marriage ends (or tax laws change). Depending on the relative earning power and adjusted gross income (AGI) of the couple, a 20-year note on their marriage benefits could easily support $33,000 or more in upfront payments.2

It’s not just useful to pay for a wedding. The existence of MBBs opens an entire new business model for dating. The underlying challenge for a company like Hinge is that if they’re too successful, their customers graduate and are never seen again. As a referral service for MBB brokers, they can get one last kickback before their success stories go away for good.

This would be hard to price

Of course, there’s an immense amount of credit risk from signing up for a 20 year marriage loan. Only about 50% of marriages make it to 20 years, an unacceptably high rate for underwriting. Terms might anchor around 8 years, the average length of marriage that ends in divorce. This roughly halves the fair value of the bond, but a couple earning low six figures can still achieve big leverage.

To avoid unexpected separation risk, MBB bond holders might put stipulations in their contract to strengthen marriages. Strong communication is the foundation of a strong marriage; MBBs might offer better rates for couples that agree to take a class on how to communicate with their spouse and set times to intentionally connect. Entrepreneurial marriage counselors might partner with MBB issuers to intervene if their investment seems at risk.

Separation isn’t the only challenge. Earning incentives for the couple become skewed; MBB sellers, a parent staying home with the kids becomes a double whammy, removing both their income and increasing payments to bond holders. The value of aligning your income with your partners’ can be thousands of dollars per year.

More challenging, the structure of the bond makes payments uncertain. Both spouses losing their job means their obligation falls to $0. It’s all the risk of a personal loan, but with a built in mechanism to stop payment when income falls. Nice for a couple, but scary for an investor.

Maybe that’s fine, depending on who the investors are. Couples could sell MBBs to their friends and family, treating it as a community-building wedding gift. Not only are they getting funding for their wedding, they’re building a diversified portfolio for their extended family.

For couples whose families don’t have the confidence, resources, or risk tolerance to buy their MBBs, going out to public investors might be the only option.

Going to market with an MBB

Given these challenges, couples might have to get creative to get new investors into an MBB.

Individual investors will demand diligence on couples seeking investment. A full dossier of the couple, including affidavits from friends and family, form the baseline to show the marriage is being entered in with good intentions. Marriage counselors can build a new line of business doing assessments of couples for institutional investors and rating agencies.

Speaking of ratings agencies, it seems logical to set up a standardized assessment system to help speed up the process. An AAA-rated marriage might look like two doctors in their 30’s with differently-paid specialties, while a subprime marriage is more like a Vegas elopement between two people who just met.

Another assessment tool might be down-payments from friends and family. Bachelor party attendees will face a lot of social pressure to invest in an MBB as a signal the groom is a good credit risk; choosing to have the party in Vegas is a negative signal.

There’s potential here for small-scale lending. But as we see in other markets – loans, mortgages, etc. — it’s almost certain that there’d be pressure to bundle these up and sell them.

A secondary market for love

As with any new financial instrument, once it’s established there will be new and exotic instruments to support them.

Collections of MBBs can be rolled into Collateralized Love Obligations (CLOs), bundles of loans to a diversified mix of couples at different income levels, years together, and psychological fear of being alone. Creative firms might even begin to put together gimmick CLOs, specializing in celebrity couples or employees in hot (but stable) industries.

To secure against default risk, separation insurance swaps would pop up to hedge exposure to shaky marriages.3 Couples therapists could put their money where their mouth is and bet on the couple surviving as a show of faith in their relationship.

There’s no reason to leave passive investors out either. An ETF, $TILLDEATH, would allow 401(k)s and pensions to get exposure to the exciting new marriage market. This actually serves as a way of betting on the overall divorce rate in the US, allowing doomsayers to put their money where their mouth is (fun fact: the US divorce rate is actually collapsing, a bullish sign for marriage backed securities).

Official idea rating

1.5/5. This could plausibly be a niche, specialized financial instrument…but it’s a little hairy. You can’t legally assign your tax refund to somebody else; technically you’re not assigning the refund specifically, but this is still a grey area with lots of potential for litigation. Beyond the IRS, consumer finance and securities law present a series of landmines for a proper MBB. Family courts won't love it in a divorce. Tax laws can and probably will change in the next 8 years.

But biggest obstacle to making this real is the unknowingness of love. Nobody really wants to get into the business of assessing a strangers’ relationship. I think the best you can do is a traditional loan with payments indexed to estimated tax benefits, a much more boring and high-interest idea.

Still, I expect some wedding finance agency out there is pitching the marriage tax savings as a reason to take out a loan at 19% APR. Maybe some competition, attracted by the tax argument, will take a little pressure off of the world’s newlyweds.

Technically after $609,350 in adjusted gross income a marriage penalty is possible, as the cutoff is only ~20% higher rather than 2x higher.

Assumptions: no change to income or tax rates, static share of income to both partners, 10% discount rate, no risk of default

I don’t think you could literally do a separation insurance swap - it would probably look more like a credit risk transfer

What happens when the couple has a marriage penalty rather than a marriage surplus? Your "two doctors" example is likely to be close to a worst case rather than AAA-rated - things like the SALT deduction and mortgage interest deduction phase out just as fast for married couples as they do for individuals, and this severely penalizes marriages.

What I really like about this post is how it gets at the heart of romance: federally regulated financial instruments