The big idea: Solve New York’s deficit with naming rights

New York City has a growing budget deficit and not a lot of time to fill it. Is the solution to put signs on everything in Manhattan?

If you’ve ever walked through Central Park, you may have noticed that some of the benches have plaques. These plaques are purchased as part of the Adopt A Bench program, one of the many ways that Central Park self-funds its operations. It’s a really beautiful program, and many of the benches contain touching tributes to memories made in this urban oasis.

It’s not cheap to buy one of these, with each plaque requiring a $10,000 donation. With over 7,000 plaques installed, this program has (presumably) raised around $70 million for Central Park operations. And if you happen to love a different NYC park, there are options for you too: most other city parks start at $5,000.

The practice of using charity to put a name on something goes back millennia. The earliest known iteration of the practice is Euergetism, the Greek and Roman custom of wealthy citizens funding public work such as baths, roads, or temples. In exchange for their patronage, donors received honors including inscriptions of their name on the infrastructure. This tradition continues today, with donors naming everything from hospital wings to college dorms.

There might be something for us to learn from here. New York City just announced a $2.2 billion dollar budget shortfall for 2026. That’s only 220,000 benches, and the city has all kinds of things just waiting to be named: street corners, lamp posts, traffic lights, trees. That’s potentially billions in naming rights just sitting around, unused and ready to solve the deficit. What if we had the courage to monetize it?

What does it mean to sell naming rights?

If this is going to solve New York City’s budget crisis, we need to understand what’s being sold. I’ll use the term naming rights to describe all versions of the practice.

The first version is corporate sponsorship: big buyers that put their names on buildings as a marketing and branding exercise. Over 90% of NFL stadiums and NBA arenas have sold their naming rights to one corporation or another. It’s a very sophisticated form of advertising, and it’s well tested.

The corporate sponsorship model has its limits — I don’t necessarily want my garbage can to have a big Geico label on it, and the aesthetics of putting a McDonald’s sign on every tree on Sixth Avenue are poor. But it doesn’t seem totally insane to sell naming rights for big pieces of infrastructure. Stadium naming rights can go for tens of millions a year; surely renaming DeKalb Avenue to State Farm DeKalb Avenue is worth something.

An alternative is the noncommercial model: Central Park benches, or the adopt-a-tree program. You give a donation, you get a plaque. These programs are both a way to demonstrate philanthropy towards the park and a way to meet an emotional need for users of the space. This comes with rules, including a standardized plaque design and (I assume) some review of content.

The philanthropic model feels more scalable. That doesn’t mean you can’t put your name on stuff — that’s the whole point! — but naming rights are more palatable when they’re not in your face. In the same way that every Central Park bench has the same plaque design, there could be a set of standardized forms that would be allowed on any individual item — a plaque, a QR code, or an online certificate of ownership you can share on LinkedIn.

The philanthropic model wouldn’t just be for the wealthy. All kinds of people have loved slapping their names on stuff for thousands of years; the ability to say that’s my storm grate triggers some primal feeling of ownership. Buyers will want to leave their mark on their neighborhood, by the fire hydrant they walk by every day, or outside the office where their boss can see.

The real question: is there enough here to get New York City to a budget surplus?

Sizing the market for naming rights

New York’s Open Data Law, signed in 2012, requires all city agencies to make “public” data available via an online portal. Using Claude Code, I pulled the latest figures for the city’s naming inventory, including traffic lights, trash cans, streetlamps, and trees. This gives us 1,475,606 namable objects.1

Now, if we charged the same for every one of these then we would need an average price of nearly $1,500 per year to close the $2.2 billion budget deficit. While I would love to have an official NDI tree, $1,500 is just too expensive.

But not all of this inventory is the same. In 2009, the MTA sold the naming rights to the Atlantic Avenue–Barclays Center subway station for $200,000 per year for 20 years. This was, frankly, outrageously cheap — in comparison, SEPTA in Philadelphia sold naming rights to a station for $1M a year in 2010.

It seems like there’s a lot of juice to be squeezed in transit. The SEPTA deal, inflation adjusted, would be worth $1.5M per year; if we average out the highly-frequented stations like Times Square with the smaller fringe stops, a conservative estimate of $2M per year on average seems fair.

We can do the same for bus shelters; while these are privatized, there’s no reason the MTA couldn’t officially name the bus stops next to them, as long as they respect their existing deals with the shelter. Let’s put these at a very conservative $100k a pop; it’s easy to imagine an aggressive buyer purchasing an entire line, turning the M15 line into the Uniqlo M15 line.

Finally, the city has over 2,000 playgrounds. It might be gauche to rename the Ancient Playground the Pampers LuxeSoft Swaddlers Playground, but sacrifices need to be made for the good of the city. At $50,000 per playground — very low for a company like P&G seeking to reach visiting parents — we can get another $100 million annually for NYC.

Just these three together would raise nearly $1.4 billion for New York City. Not bad! Unfortunately that still leaves an implied price of $555.92 per year for the rest of the inventory, far too high for every tree and manhole cover in the city.

There is one piece of high-value real estate that we haven’t monetized yet: street names. New York, famously, uses numbers for many streets and avenues. This is a great thing for wayfinding, but is not revenue maximizing for the city.2

With street names on the table, every direction, address, and signpost suddenly becomes an advertising opportunity. Sure, you might need long-term contracts to avoid changing people’s addresses too often. But it’s clear that there’d be demand for naming rights among a set of high-traffic, high-commercial-value streets. Obvious choices include Macy’s Fifth Avenue and JP Morgan Wall Street. After a few years, would anyone even notice?

The value of a street name is massive. Every time someone takes a left on the Pepsi-FDR drive, Google Maps is going to read out an advertising moment. Given the commercial value implicit in these naming deals, let’s assume we can sell 25 of these for $15 million each. That gets our total big-ticket revenue to $1.75 billion, and the price per remaining unit to $300. That’s only $25 a month to put your name on the storm grate near your house!

We did it. New York City’s deficit is solved.

Unfortunately, there’s more complexity

New York is, for better or worse, a city where economic value is concentrated in Manhattan. In general, higher property values indicate more foot traffic and wealthier neighborhoods; the Financial District probably has higher naming rights demand than suburban Staten Island.

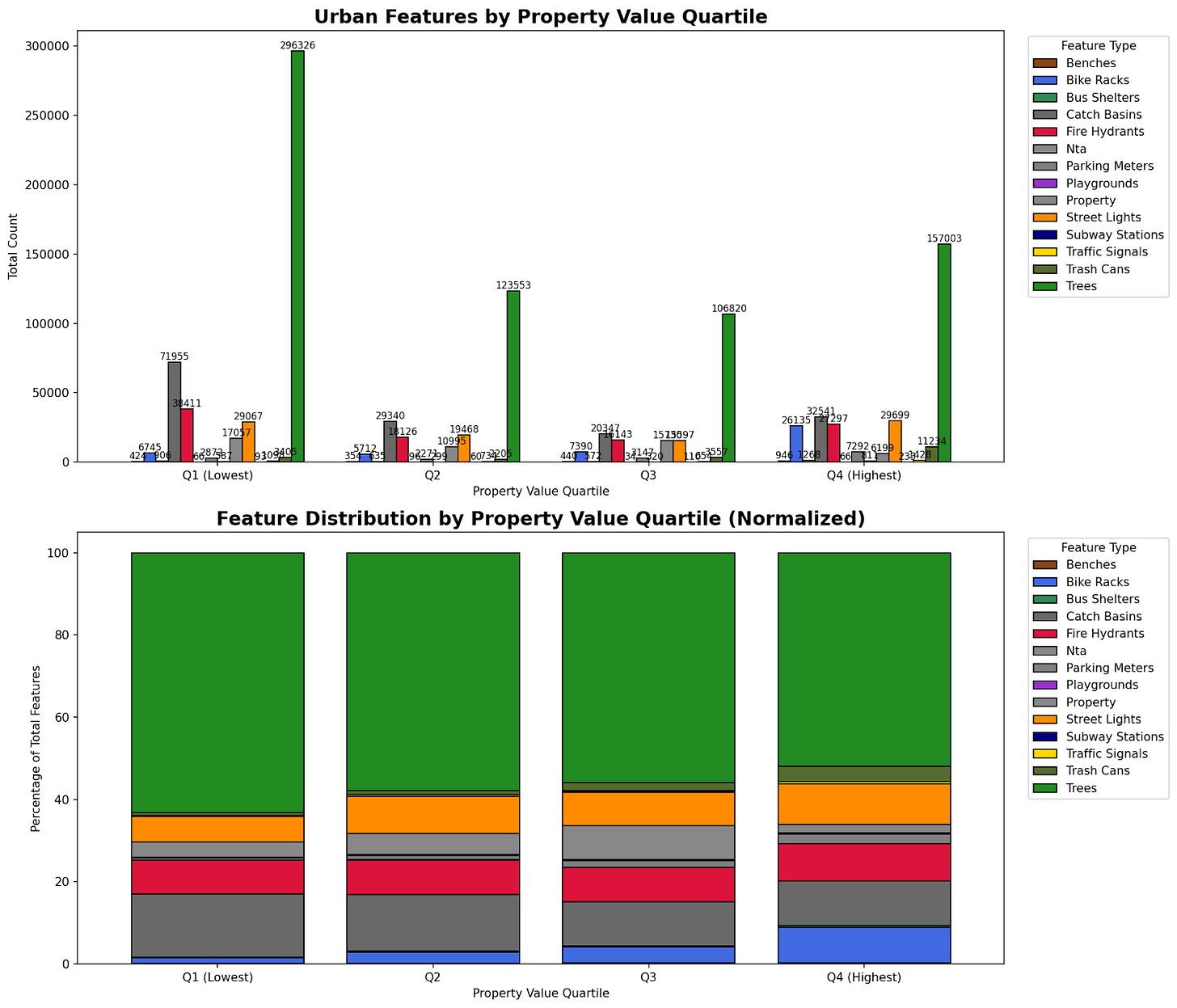

I pulled NYC’s public data on every piece of public infrastructure and mapped it against property values. The results are, unfortunately, not great; it looks like the bulk of inventory is in the lowest property value areas.

Given poor location density, it seems unlikely that all 1.4 million things will find buyers. Only about 70% of Central Park’s benches have been adopted, and that’s the highest value location in the whole city. Lower value areas are going to come in at less than that; if the city averages 25% adoption, we’d need to charge $1,200 a year, or $100 per month, for every piece of inventory.

Even this might be too optimistic. We’re putting millions of things to name on the market all at the same time. Flooding the market in this way would collapse the price, a terrible outcome if trying to close an in-year budget gap.

The good news is, I don’t think we’d get that far.

People would absolutely hate this

While there may be an economic logic to this, it’d fall apart in every other way. Politically, the first politician to support selling naming rights en masse is going to be vilified as the ultimate corporate sellout. It’s easy to imagine vandalism of new signs and fights over content; I don’t want to have to adjudicate if a message on a tree is too political, and I don’t think Mayor Mamdani does either.

The quality of life impact would also be significant. There really is something special about public spaces; a few heartfelt (and aesthetic) plaques are fine, but if we actually cover the city in endless logos and signs, it sort of kills the vibe

The disruption would go beyond aesthetics. Imagine the constant partial street closures for installation, vandalism and subsequent lawsuits clogging up the New York court system.

Enforcement would also be a disaster. The city has a vested interest in making sure that the plaques aren’t a nuisance; you’d need to hire an army of enforcers, constantly reviewing the streets and responding to 311 complaints about “deez nuts” plaques that snuck through the review process. NIMBYs would complain that signs are destroying the neighborhood character of Greenwich Village. Harassment is impossible to manage; you don’t want revenge plaques going up after every breakup.

In the highest-value areas, name-squatters could start buying naming rights to flip. This is the real danger of a naming regime: scalping. Selling naming rights to a fire hydrant doesn’t do New York’s pre-K funding any good if a middleman is capturing thousands of dollars for a plaque spot they got in the initial sale. A clever entrepreneur could even buy out the entire inventory of a neighborhood and effectively re-create a billboard business, collecting rental income as a hyperlocal monopolist.

You could even begin to see bad actors using their inventory to hold buildings hostage. Does it hurt a restaurant if the tree in front of it says “don’t eat at Al’s?”

Official idea rating

1.5/5. While I would love to say that the No Dumb Ideas newsletter solved New York’s fiscal problems, the operational and social complexities are probably a little too high to make this work.

Still, this gets an extra half star for being a good way to fund nonprofit infrastructure. In a world of deepening budget cuts across the things that make a city nice to live in, it seems natural that we’ll see increasing reliance on donors. If someone wants to pay to keep a playground open, I’m ok giving them a little token of appreciation.

Sadly, manhole covers had to be an estimate; for whatever reason this is the one piece of data I couldn’t find on NYC Open Data

New York actually has a tradition of honorary street names for individual blocks, although not all of them have an accompanying street sign

Scalping could be somewhat solved by auctioning off the high value spots (not the auction would be universally known and there wouldn’t be any resales) so that you don’t sell below fair value. Anyway the much simpler solution is to charge for parking. 3 million parking spots for 60/month on average gets you there and is incredibly cheap parking

Solid thought experiment. The spreadsheet approach to quantifying naming inventory is clever, but the enforcement nightmare you flag is the real issue. I used to work near a park with sponsored benches and even thos modest plaques drew occasional vandalism or disputes. Scaling to 1.5 million nameable objects turns the city into an admistrative black hole. The scalping risk is wild too becuse it basically recreates landlordism for street furniture.