The big idea: Spread out New Year’s resolutions

It’s a cliche that gyms get packed with hopeless newbies every January, doomed to cancel their memberships. Smoothing out demand might give them a fighting chance.

Every year, dozens of newspapers publish the exact same story about how nobody keeps their New Year’s resolutions.

It seems like resolutions should work. Adjacent ideas like Dry January work by creating a social permission structure for alcohol-less activities. The solidarity and excitement of doing something hard together is a great motivator and social bond.

So why the annual resolution failure articles? I think they’re actually about gyms. Per Statista, the most common resolutions this year included wanting to exercise more (48%), followed closely by eating healthier (45%), and losing weight (31%).

Unlike our other examples, gyms are a congestible good; after reaching capacity, every new member makes the experience worse. Classes fill up, equipment gets lines, and the experience degrades for a few miserable weeks until February, when things get back to normal.

This is totally backwards. Concentrating all of that New Year energy into January makes the gym worse at the exact moment most new joiners are trying to build a habit. There has to be a better way to utilize this limited pool of motivation.

The evolution of resolutions

The concept of a New Year’s resolution goes back to the ancient Babylonian tradition of Akitu, taking place during their New Year in April. During the 12-day festival, farmers made promises to the gods to repay their debts and returned borrowed farming equipment. If they kept their promises, it was believed they’d be rewarded and vice versa.

The festival was adapted by the Romans, who made offerings to the god Janus while promising good behavior. The festival was moved to January in 46 BC, when Roman calendar reforms created the New Year date we know today. Over the centuries the tradition has evolved to be increasingly secular, with resolutions looking more like “start recycling” than “improve my spiritual fortitude.”

But far from the lofty ideals of Babylon and Rome, today’s New Year’s resolutions are — arguably — just an ad for the fitness industry. It’s common for new signups to increase as much as 30% in January, driven by an advertising campaign demanding that you pick up a new habit and get rolling right away.

Unfortunately, around 80% of those joiners quit within 5 months.1 This is sometimes treated as a moral failing, as if the people who get a boost of motivation on January 1st are too ill-disciplined to actually become fit. But it seems to me that the congestion that comes with the resolution rush is an underdiscussed contributor — you’re not going to build a habit if you have to wait 20 minutes for a treadmill!

January is really a coordination failure masked as a personal failure. What if we could solve it by getting people to start their resolutions later in the year?

A solution for overcrowding

Typically, an increase in demand like we see in January would imply an increase in prices given a fixed capacity. Instead, gyms all lower their prices in January to compete with each other. I don’t blame the gyms — they have high fixed costs and low marginal costs, so obviously they want to lock in long-term members while they’re looking — but it’s an inefficient equilibrium for everyone involved.

Instead of offering a January discount, gyms could offer a discount to delay starting a membership until later in the year. Need to start in January? Full price. Patient enough to wait for a slow month like March? 15% off, and initiation fees are waived.

The gym gets your commitment — and your first month prepaid — but doesn’t face a capacity crunch. This could even be dynamically adjusted based on demand; if October becomes a particularly low-uptake month, the discount could automatically increase to smooth out utilization.

Part of what gyms are selling during the New Year is the feeling of commitment and movement towards a goal. The delay might not be for everyone, but for the right person the act of buying a membership might be enough to feel progress. And when they do start (one to eleven months later), they’re entering a much better environment.

A delayed start date changes the entire experience for new joiners by giving them a clearer sense of what being a regular goer feels like. Gyms might begin to offer onboarding classes for each start date, creating a stronger structure to stick to the habit (and retain the membership). In contrast to someone selling you a membership on the expectation you’ll churn, making you wait so you’re successful signals they want you to succeed.

The finances are appealing too. Back of the envelope math implies there are around 3 million New Year’s joiners per year.2 If we assume a conservative average membership fee of $55 per month, January joiners alone would spend $330 million more per year if the average joiner stuck around for just two additional months.

Actual results could be even bigger. Industry roundups commonly cite an average membership tenure of 4.7 years, or around $3,102 in total dues. Just 10% of a year’s January sign-ups becoming like an average joiner is worth around $825 million in incremental lifetime dues per year.

Spreading out memberships implies other changes to the gym business

There are a few issues to address with delayed start dates, but the biggest one is that life happens. People move, get injured, or lose their motivation. If they simply cancel before their start date, a gym loses a customer that otherwise would have paid for a few months.

There are a number of solutions that gyms could try: cancellation fees, start date swaps, or membership freezes until a later date. But all of these add risk to the gym’s ledger; delayed starts will fall apart if there’s any risk of losing that customer. The only lever gyms really have is to make cancellations functionally impossible. If a $55/mo membership is sold, it needs to be ironclad for a delayed start to work.

Making cancellations hard isn’t a new idea — gyms are famous for it — but it infuriates customers. If there’s no cancellation, there needs to be an escape hatch: make memberships fully resellable.

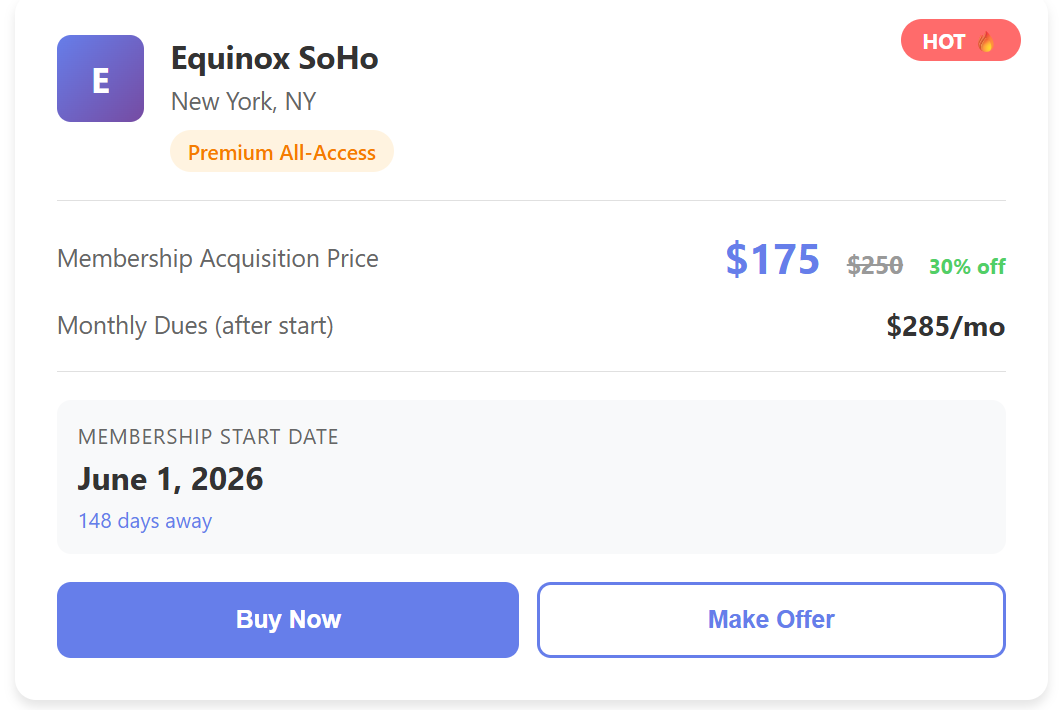

Imagine a platform — let’s call it GymEx — that lets users buy and sell their memberships. Each membership, when issued, would be given an unique ID that ties to your deposit, a set monthly fee, and a specific start date. Ownership of the ID can be transferred, integrating with whatever identity verification system is used by the respective gym.

The ability to resell means that gyms can confidently predict their total member count and revenue for the year, even if the actual owners of those memberships change. For customers, it makes cancellation easy, straightforward, and potentially lucrative. Of course, it’s always possible that you’ll have to sell a low-demand membership at a loss — or even pay someone else to take it.3

The ability to see market-clearing prices for memberships totally reinvents gym economics. Sophisticated clubs can develop a model of the relationship between membership levels, monthly fees, and initiation fees. By better balancing these three levers, gyms that adopt dynamic pricing will be able to maximize their revenue and make tradeoffs throughout the year.

Gyms could even begin to experiment with other variables for memberships beyond start date. Some memberships could have built in fee increases over time, or limited-time memberships (e.g. a 3 month plan for the summer) that let them capture increased demand without committing to long-term supply increases. Indefinite memberships could be issued to early joiners, although this perhaps risks some inheritance issues if it’s a true perpetuity.

Gym memberships as an asset

The ability to resell implies a right to ownership, essentially making gym memberships into assets. Given the second most common resolution after fitness is saving money, this is a slam dunk. Joiners in January can knock out two resolutions for the price of one: they get the dopamine hit of starting their fitness and they made an investment. For gyms that rely on exclusivity, like Equinox, creating an appreciating asset actually adds to the status of being a member.

This dynamic shifts gyms from being sales organizations to being market makers. When capacity is high, gyms can issue new memberships. When demand outstrips capacity, gyms can buy back memberships, driving the price up and making them available for resale. Customer acquisition is decentralized as existing members promote the gym, substituting for the expensive sales staff.

With a vibrant trade in gym memberships rolling, speculators are sure to come in. Professional membership-flippers could emerge from fitness influencers who buy up memberships before using their platforms to drive demand for their fitness clubs. Shortages of memberships at peak times of the year could drive massive price appreciation, before crashing as members cash in on bubble prices.

As the financial ecosystem develops, there could be more creative outcomes. People with injuries might opt to rent out their memberships; if they have a particularly attractive monthly rate, they might be able to find arbitrages and actually make money out of the deal. This sort of implies the evolution of a taxi-medallion type structure with magnates collecting rent on people going to their weekly yoga class.

If gym owners keep watching other people get rich off their memberships, they’ll want to fight for a bigger piece of the pie. This might start through a commission structure for resold memberships — 15% of the sale price seems reasonable — but could expand to active market manipulation and the creation of in-house trading arms. I don’t know if gym memberships are legally a security today, but the SEC certainly is going to get involved if New York Sports Club is regularly manipulating the market for their memberships before issuing new stock.

Official idea rating

3/5. January congestion is the graveyard of motivation. It seems better for everyone involved if we really can distribute gym start dates throughout the year, even if it requires a discount.

But the existing culture of gym management is probably going to struggle to adapt to not closing a member immediately. It’d take a forward thinking gym to try it and an even more forward thinking gym to accept decentralized ownership of membership, especially if they see other people making money off of it. This is likely the domain of a quirky, high end, and exclusive gym owned by someone that loves publicity. If that’s you, reach out — I’ll be first in line to buy a membership as part of a diversified portfolio.

I was a little skeptical of the sourcing on the ‘80% quit in five months’ stat, so I talked to two gym owners before writing this; they told me that if anything, the 80% churn happens faster than that.

The HFA found that gym memberships went from 68.9M in 2022 to 77M in 2024, an average of around 4 million new members a year. But with an overall 71% retention rate for health clubs, that implies there are around 25 million net new memberships per year. With 12% of new memberships coming in January, that implies around 3 million New Years-adjacent joiners annually.

Being good at asset management is probably a strategic lever for fitness studios, but it can also be dangerous if handled poorly. If the marginal price for a Planet Fitness membership is consistently negative, it actually begins to devalue the brand (“people are paying to stop going to Planet Fitness”).

Fun take! But I don't think postponing sign-ups is the only hurdle from the gym's perspective - the modal business model seems to be that people who actually go to the gym are loss leaders for the people who sign up and never use the equipment, so making it easier for people to stick with the habit is in some sense a bad thing (or at least will raise costs for everyone) https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2014/12/17/371463435/episode-590-the-planet-money-workout

It's so hard to book workouts in January, this would help the regulars!